Too High to Survive

The Regulatory Cost of California Cannabis

by Darius Kemp

Executive Summary

California’s legal cannabis marketplace, once heralded as a pioneering industry, is now facing a crisis driven by excessive taxation, overregulation, fragmented dual licensing concerns, and capital inaccessibility. This white paper, developed through qualitative interviews with industry operators and an analysis of economic data, investigates the structural inefficiencies that have destabilized cannabis retail, particularly among social equity licensees, and proposes actionable reforms. Despite high consumer demand and over $1 billion in annual state revenue, the majority of cannabis operators struggle to remain profitable. Retailers, especially those participating in social equity programs, face startup costs over $1 million, financing at interest rates as high as 30%, and tax burdens that drive consumers to a flourishing unregulated market. Regulatory requirements such as mandatory product testing and the CCTT seed-to-sale tracking system further strain business viability without commensurate public benefit. The paper argues that California’s cannabis market is not inherently anti-competitive but structurally unviable for most retailers under current policies. It offers three reform scenarios, from maintaining the status quo to a comprehensive systemic overhaul. The most practical recommendation—Scenario 2—calls for reduced taxes and fees, streamlined licensing, improved access to capital, and a restructured social equity framework. These changes could boost annual profitability by over $100,000 per retailer, revive consumer participation in the legal market, and improve long-term sustainability. Without immediate and coordinated intervention from state and local governments, California risks losing the businesses it sought to empower through legalization, threatening public safety, economic development, and equity goals.

Definitions

- CCTT California Cannabis Track and Trace uses unique identifiers (UIDs) to report the movement of cannabis and cannabis products through the licensed commercial cannabis distribution chain.

- DCC Department of Cannabis Control - the California agency that regulates the state cannabis marketplace, licensing, and policies.

- Legacy Operator - colloquial term for people who sold cannabis during the state’s prohibition and illegality period. They may have also been incarcerated for engaging in these activities.

- SF OOC - San Francisco Office of Cannabis is the city’s cannabis regulatory body. Regulated/Unregulated - terms that denote the legally authorized regulated cannabis activities versus the still illegal unregulated activities that occur in the underground market.

- Licit/Illicit - see regulated/unregulated.

- Social Equity - efforts support people and communities harmed by cannabis criminalization. These efforts lower barriers to the cannabis industry for those hit hardest by the War on Drugs.

Methodology

This white paper employs two primary methods for analyzing the California cannabis industry and the influence of taxes and regulations on the legalized market. Focusing primarily on qualitative interviews of industry experts from large multi-state operators (MSOs) to smaller local cannabis company owners, to understand the impact of taxes, regulations, and conditions on the ground that determine the success or failure of a cannabis retail store. Secondly, I reviewed academic articles, reports, news articles, and other periodicals to collect quantitative and qualitative data on the state of the California cannabis industry. Also, it is essential to note that I will only focus on the costs and status of the retail portion of the supply chain.

To investigate this problem, we will focus specifically on the market's retail sector. Because retail has the lowest margins in the entire supply chain, and since most social equity programs are located in urban areas, retailers hold the majority of equity licenses. Couple this with the current crisis in retail tax remittances, with a “15.4% default rate on the excise tax, this means roughly 250 retail businesses throughout the state … are behind on either all or part of their tax obligations”1, making it clear that the retail sector is a key component that must be addressed to begin improving the stability of the market.2

Introduction: Cannabis in California

Medical cannabis has been legal in California since the passage of Prop 215, the “Compassionate Use Act”, authorized by voters in 1996. With the world’s first and thriving medical cannabis industry created in 2016, voters went back to the ballot and approved Prop 64, the “Adult Use of Marijuana Act”. This was the beginning of a spark across the United States, challenging the status quo of the “war on drugs” started in the 1980s by President Ronald Reagan and championed by his wife, First Lady Nancy Reagan at the time. What is evident now is that the drug war was a failure, and attitudes on cannabis consumption in the U.S. have been flipped upside down. Currently, 54% of Americans live in a state where adult-recreational cannabis use is legal, with a total of 74% living in a state with either adult-recreational or medical use.3 Despite polling numbers and the fact that states are moving towards legalization at either the medicinal or recreational level, the federal government has barely moved on the issue. In 2024, President Biden initiated the process of rescheduling cannabis from Schedule I to Schedule III. While the second Trump administration has stated support for descheduling and even decriminalization, his administration has placed roadblocks through actions by the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA).4

Nevertheless, until there are legislative and executive actions, the cannabis industry nationwide will still suffer from the de facto penalties created by continuing federal prohibitions. Currently, cannabis companies are restricted from utilizing any federally insured (FDIC) financial system because of the risk banks face from working with “illegal enterprises”. Instead, they depend on predatory banks, venture capitalists, and other private lenders. This highlights a serious externality of the California cannabis industry that can only be corrected in D.C. by Congress; however, there are still areas where California can improve the business environment for legacy operators and existing firms.

1.1. Current State of California Cannabis

When examining the current state of cannabis, we must focus on two distinct groups: consumers and operators. They are the primary drivers of the market's existence, notwithstanding the role the government plays in designing the legalized marketplace. They also bear the brunt of taxation that can discourage or attract consumers to the market, and the highest number of licenses are distributed to this category.

1.2. California Consumers

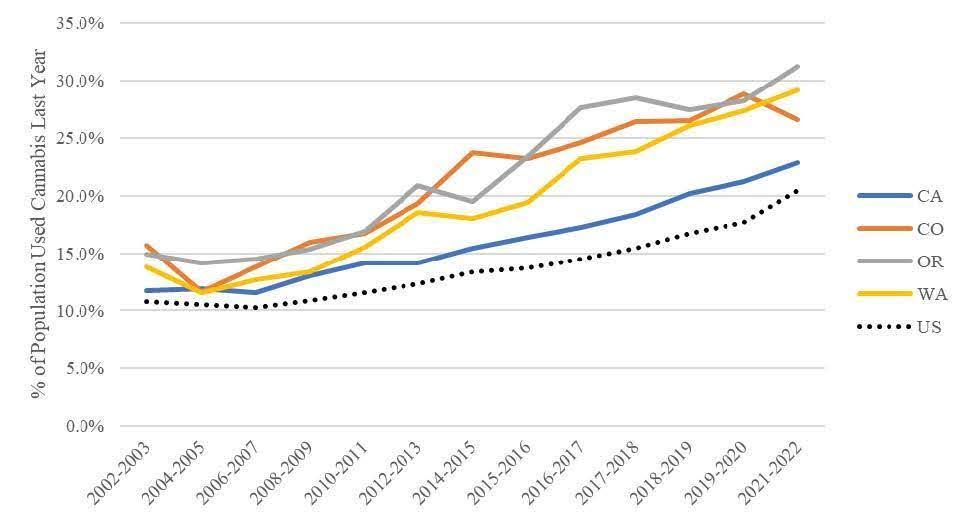

Consumption and approval of cannabis have been steadily on the rise since the adult-recreational use was legalized. The chart to the right is the National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH) Prevalence of Past-Year Cannabis Consumption, Unadjusted.5 It indicates that cannabis consumption in California, while lower than in other Pacific coast states, was roughly 11% in 2002-03, and has risen to approximately 25% as of 2021-22. This is a strong indicator that the state's legalized and regulated market is robust, with potential to grow even further, considering the untapped potential still in the unregulated market. ERA Economics, a consulting firm hired by the California Department of Cannabis Control, estimates that the “total value [unlicensed cannabis produced in state] is around $11.9 billion ($2.0 billion within the state and $9.9 billion exported)”6. This indicates that the licensed regulated market of $5.43B as of 20237 has at least $2B in additional market capitalization, which is being untaxed and in the unregulated market because consumers have been able to find lower prices and ease of use.

Interviews and analyses of conversations with experts indicate that California cannabis consumers have easy access to the unregulated market, which is a significant deterrent for investors and is stunting the growth of the market. A simple Google, TikTok, Instagram, or Weedmaps search highlights the locations, dates, and times of events the industry refers to as “Seshes.” These events are held in public places, some near police stations, demonstrating California law enforcement's nonchalant and hands-off approach to the issue. The Department of Cannabis Controls also mentions this as a serious concern for the industry, highlighting that “plant eradications in California are estimated to represent between 6.9 and 16.8 percent of unlicensed production that is cultivated in the state for 2011–2016, and between 7.5 and 18.3 percent for 2019–2024.”8 These amounts barely put a dent in the unregulated market which underscores that more law enforcement and a reignitions the “war on drugs” would not solve the provlem of a vibrant underground unregulated cannabis market in California, that is easily

accessible to most people.

1.3 California Operators

Operators in the California cannabis industry are struggling to remain afloat, but that was not always the case. Considering that, “2016 was irresistible to cannabis entrepreneurs… capitalists wasted no time investing billions into California’s pot market.”9 Cultivation and retail were the early crowned jewels of the early stages of the industry, with companies like MedMen opening “Apple-like” stores with investors promising that they would “virtually print money.”10 Those days were short-lived, and now many cannabis firms/operators are either struggling to survive, are out of business, or utilizing the unregulated market to make ends meet. In an interview with an expert in the field, they noted that “95% of the income they make comes from 'direct-to-consumer wholesaling,'”11 which is a euphemistic way of saying selling on the unregulated market.

From 2020 to 2024, there has been a steady decline in the retail price of the baseline product, dried flower, going from a high of $39 per 1/8th of an ounce to $23 per 1/8th. Typically, we would attribute declining prices to innovations in the market or health competition. These downward price pressures stem from the unregulated market, overproduction, and oversaturation. While we have already discussed the issue of increased enforcement in the unregulated market, poor business practices and rushed venture capitalist investors, mixed with a harsh and complicated regulatory system, also contributed to creating these conditions for California operators. One expert went so far as to say that a significant problem with the industry was too much capital and “not enough adults in the room making decisions,” while also highlighting the oversaturation of licenses due to unlimited access created by the DCC and local governments.12

Additionally, the burden of taxes and regulations on the cannabis industry is overwhelming firms' ability to make any profit, harming the efficiency of the marketplace. A report from the DCC13indicates that the state currently has more cancelled or expired licenses than active ones across the supply chain. Industry experts are concerned about the industry's current pricing and taxation trends. Consumers are apprehensive about prices, and the legalized market has higher rates that push people into the unregulated market. With these conditions, the state's goal should be hyper-focused on supporting the capital financing pressures in the industry while reducing taxation and regulatory burdens to allow the industry to grow and sure up the market.

1.4 Social Equity

An important subsection of California operators is social equity, which the state has designated as an area of support essential to California’s market. But what is social equity in cannabis, and how does it impact the health and viability of the cannabis market? Often, people refer to social equity as reparations for Black people or charity for individuals affected by the “war on drugs.” Social equity is a process of the government providing certain business advantages to people impacted by the “drug war” and traditionally marginalized in entrepreneurship. This differs from a rural business program for small-town economic growth or women's business programs to increase female ownership.

The state adopted a light-touch approach in California, allowing cities and localities to determine whether and how they will implement a social equity program. The requirements generally include a residency within specific historically impacted zip codes, income limits, and/or a conviction for cannabis possession. In comparison, there may be more or fewer requirements based on local laws. However, the ultimate goal is to allow state residents to start a business in an industry where they were previously penalized. Opponents of social equity programs have argued that this is a “form of economic protectionism that limits competition and leaves small local operators vulnerable to predatory out-of-state partners and investors.”14 While I agree that some predictions of local operators being vulnerable to larger, predatory entities are valid, states often tilt the business landscape or regulatory market in a specific direction for various economic, cultural, or social reasons—for example, through the establishment of monopolies in garbage collection, subsidies on crops, or the creation of opportunity zones. California has created laws and regulations to codify social equity as a goal, alongside the health and viability of the cannabis marketplace. Therefore, as we proceed, it is essential to understand that any corrections or improvements to the industry must include the protection of the cannabis market's social equity sector.

What Forces are making California’s Cannabis Market Anti-Competitive?

Cannabis legalization has increased state and local tax revenues by approximately $1 billion per year since the passage of Prop 64. However, the state is seeing a decrease in active licenses, as companies use extraordinary measures to remain in business due to regulatory demands, and a constriction in capital markets, which is making it difficult for some companies to remit taxes effectively. Industry reports highlight that “$243.5 million in default is attributable to cannabis businesses that had licenses and were open at any point in time in 2023.”15

With firms abandoning licenses, going bankrupt, and leaving large unpaid tax bills, California’s cannabis marketplace is unhealthy, causing harm to citizens employed in the industry, business owners, and the state’s goals. To that end, this white paper, funded by the DCC, is meant to investigate anti-competitive forces impacting the industry's health. I have found that this framing of anti-competitiveness is a misnomer because competitive is not always the primary goal of a market; rather, we consider things like, whether there is equilibrium in the marketplace, whether services are being delivered efficiently, or if a monopoly exists, whether it is gouging consumers, amongst other criteria. Instead, I would argue that the California cannabis marketplace is too overburdened by misaligned state/local regulations and taxation, coupled with the high cost of business capital financing, making it difficult for license holders to succeed. My objective is to define and explain the core issues that have created these conditions for cannabis retailers in California, and then provide policy recommendations to rectify observed issues.

2.1 The Profit Problem

The most important takeaway from this model is that it is an economic loser for any intelligent entrepreneur. No sane person would choose to open a business with a loss of approximately $55K, contend with high taxes, in a federally illegal industry, and have an escalating number of armed robberies and break-ins20. With just one major crisis, like a robbery, debanking because of federal restrictions, unpaid supplier accounts, etc., operators are likely to enter into even more debt with very few financial options to manage it.

For example, the profit margin quickly disappears when the same model is utilized and some core variables are changed. Because it's San Francisco, and your location is in a high-crime and large unhoused community like the Tenderloin neighborhood, and you need armed security, the cost increases to $200k. Your interest rate on a financing loan from a VC firm goes to 27%, and rent goes to $25K a month. Under current market conditions, that would result in a deficit of —$300,000+.

The core problem with regulated cannabis retail is the inability to earn a reasonable profit. For California, the most optimal outcome of creating a legalized cannabis industry would be its normalization, so that opening and financing a dispensary would be like a bar or restaurant. However, that is not the case because capital is difficult to find, and profit margins are virtually nonexistent. Utilizing the profit maximization model, I created a scenario to project the business environment for cannabis operators. My model makes some basic assumptions about the cost of starting a dispensary in San Francisco, listed below, based on interviews and conversations with over 10 experts in the field. Additional details are noted in (APPENDIX #1).

The cost of capital is calculated16 $\frac{P\times \frac{1}{12}}{1-\left(1+ \frac{1}{12} \right)^{-(T-12)}} $. To determine the variable cost per unit (VC) sold, I use the current wholesale price of ⅛ oz of cannabis flower ($13) and multiply it by the tax rate, utilizing this formula17 VC = W(1+X) for a VC cost of $17.70 per unit. Total revenue was based on the assumption that this retail local would sell $1M or less of roughly 70K units of product annually at an industry-standard retail markup rate of 2.5 times the wholesale price. To determine this, I used the formula18 AQ(RP-VC) = TR. Lastly, I calculated the profits/losses by19 TR-FC = Profit.

Profit Maximization Model

Annual Fixed Cost

Cost of Capital

Variable Cost of ⅛ Flower

State Licensing fees/app - $13,500

Wholesale Flower price per unit $13

Local Licensing fees/app - $10,000

Interest Rate - 20%

State & Local Cannabis Taxes combined rate - 34%

Staffing - $260,000

Term of Loans - 60 months

Total Net Revenues - $1,001,300

Capital Expenditures - $768,700

Annual cost of capital - $26,000

Principle Startup Cost - $1,000,000

Annual Profit/Loss - ($56,000)

Some key factors to note are the higher licensing fees and application costs. State application costs for opening a bar that sells beer and wine in San Francisco would cost $1,500, with annual licensing fees of $1,100. Local licensing in SF is high for selling alcohol, with one-time costs between $150-300k, but this is also a conventional business with more options to finance and manage debt. Also, capital cost rates are exceptionally high in the cannabis industry, unlike the hospitality field, being between 17% and 30%, because of the risk of losing federal banking insurance (FDIC) due to its illegality. For my model, I used the lower end of that scale. Finally, the combined taxation rate that the consumer pays is 36%. That includes a state cannabis excise tax of 15%, state sales tax of 7%, SF cannabis tax of 8%, and a sales tax of 5%. This amount will fluctuate depending on the location of the dispensary. Still, tax rates of 30% and over, generally viewed as deterrents for many consumers, help to prop up the unregulated illicit market that the state desperately wants to terminate. When we return to this model, the profit problem is the primary focus of my policy recommendations.

Systems of Failure

3.1 The Road to Retail

Three main components have exacerbated the decline of the California legalized cannabis market: overcapitalization and commodification, local control, and taxes and regulatory policies. While they were all siloed with very different decision-makers within each, they have collided to create the perfect storm for retailers. Common sense dictates that most people would not start a business that is structurally proven to lose them money. Most people start companies in fields with strong fundamentals where they can predict profits and losses, such as a convenience store, content with steady profits and growth. Or they enter a risky market with gigantic potential, such as cryptocurrencies, gambling on their ability to strike it rich.

However, cannabis retail is currently a losing proposition in California. Using the profit maximization model, I have observed the current economic challenges of the marketplace, outside of the two most significant externalities: federal legal prohibition and a vibrant illicit market. Below, I have illustrated the process model for opening a cannabis retail store in San Francisco. Several important aspects of this process determine much of the initial capital cost to operators:

- Operators must secure a retail location before applying for a San Francisco or state license. While this requirement is potentially waived, it is a crucial cost driver because of location restrictions, which create predatory landlords who raise rates for cannabis businesses.

- Like many localities, San Francisco requires community improvement work to be done at the store's cost and with input from residents and nearby companies. This paternalistic rule is unnecessary in most other industries, adding time and costs to a struggling sector.

- Lastly, the local process must occur before state licensing can begin. In this process, companies have been approved for local licensing, which have gone on to be stalled or denied at the state level, adding additional bureaucratic steps, time, and resources that firms do not have.

3.2 Over-Capitalization & Commodification

After adult recreational use was legalized, retail was one of the most sought-after licenses due to the expected exponential growth of the marketplace, with an estimated growth rate of 9.4%.21 This flood of resources and capital from investors created what was known as the “green rush.” Social equity operators were inundated with offers to partner with, or outright sell their licenses for tens of thousands or even millions of dollars. Reportedly, companies like Eaze would raise over $800M in their Series D round, and PAX was able to raise $420M in their Series A.22 At Eaze’s peak, they had annual revenues of $200M, while losing $230M annually.23 The most well-known example is MedMen, called the “Apple store of weed” by many. By going public on the Canadian stock market, they raised over $110M, and were valued at $1.65B in 2018. Today, the company is overrun with lawsuits, has over $137 million in debt, and has only $15 million in cash.24 At this early stage in California, competition was fierce, and gaining market share was all that most companies wanted. They were willing to lose millions of dollars annually to outlast the next company and be one of the survivors of this initial green rush.

This marked the beginning of the market's overcommodification, leading to valuations that would ultimately crash the California industry. More companies entered the market, leading to overproduction, which caused a price collapse. As opposed to today, where capital investors are scarce, and financial institutions that lend to cannabis companies have interest rates that start at 17%. Leaving the state to be broadly seen as a cannabis money pit, to venture capitalists and hedge funds, who were the original capital funders between 2016 and 2021. Additionally, this makes it difficult or impossible for social equity operators to raise funds to enter the market, a key economic priority for the state.

As the chart above highlights, the quarterly price of cannabis product sales, as oversaturation proliferated, prices dropped, creating economic surplus for consumers by taking it from producers. Ultimately, this placed the most pressure on retailers who were already competing with a vibrant and lower-cost, unregulated market, resulting in the most significant decline in the number of cannabis business employees compared to other states between 2023 and 2024.25 This demonstrates the seriousness of the impact of overcommodification and overvaluation on a market, as capital markets have retreated from California due to billions of dollars in lost investments. Current business financing rates in California for cannabis are between 17% - 30%, even for financially solvent firms, making the cost of capital too high for many.26

3.3 Local Control

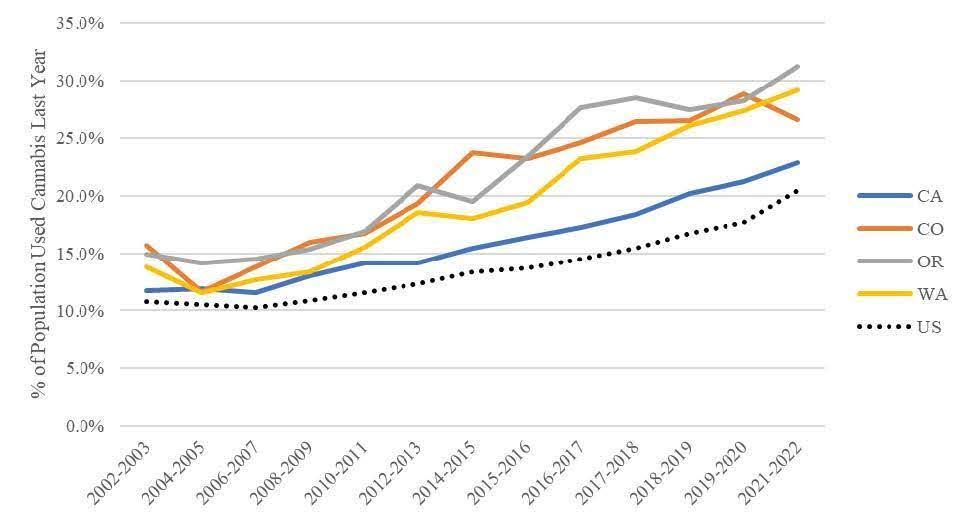

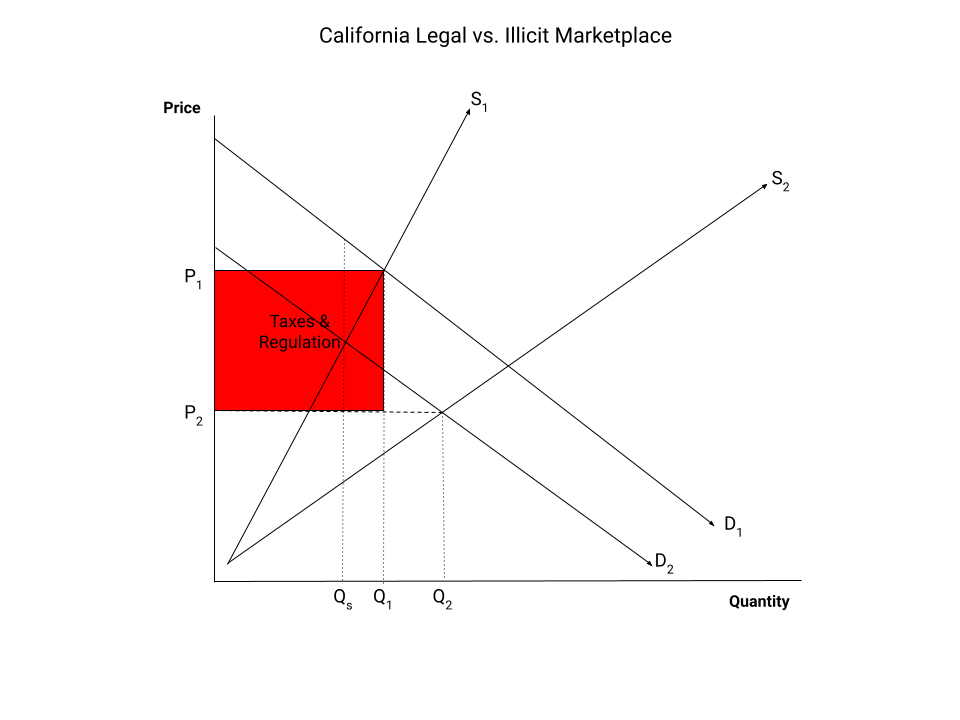

The process of creating effective industry regulations was hampered by special interest that would cripple the long-term growth of the industry. While the trends are evident that most Californians have no objection to the use and sales of cannabis in their communities, there is still a vocal minority in political leadership that either have moral or other reasons for disliking the new normal of cannabis legalization.27 Many California medium to smaller cities have had a “history of local bans on all cannabis businesses,” with many stating that crime prevention, restricting access to children, and local aesthetics are the primary reasons.28 Initially, local control was a way for proponents of Prop 64 to ease concerns by local mayors and city councils on their ability to manage and control cannabis activities in their jurisdictions. However, this has spiraled out to be a cudgel to wield against some legally authorized cannabis business activities in their locations. The chart below, from a supplemental report from the DCC, illustrates the roadblocks and barriers localities impose on lawful business activities for their purposes, which hinder the state from meeting its revenue and equity goals.29

Experts bemoaned what they have observed as cities and counties believing that they can use cannabis as a “piggy bank”.30 This idea echoed through all qualitative interviews of industry experts in and outside of the state. This indicates the disconnect between the government regulators and the industry itself. The California League of Cities has long advocated for local control, lobbying effectively on local taxation rights, community benefits requirements, and local licensing requirements. As my profit model demonstrated, local governments have increased the cost to consumers by adding cannabis taxes and general sales taxes, making the regulated market economically unattractive to consumers who can easily find unregulated operators selling the same products at half the price with no taxes. At the same time, business owners have argued that these rules are killing their businesses and reducing local tax revenues, hindering governments from maximizing potential benefits from cannabis sales. The underlying issue is that a nascent cannabis industry in the original days of adult-recreation legalization was tied down before it could take flight.

3.4 Taxes & Fees

The California DCC continually highlights that cultivation and production of cannabis are up, while simultaneously stating that, “despite annual increases in cultivation volumes and consumption, retail sales of licensed cannabis have been decreasing since 2022”.31 They argue that this is because reduced retail prices are lowering the value of current sales, while the number of units sold is steady. Both are still poor outcomes for the state, with over $2B in unregulated sales annually. Experts and analysts alike agree that overtaxation is a primary driver in the unregulated market that is keeping an estimated 60% of the California cannabis market in the unregulated sector, with a compounded tax rate (depending on jurisdiction) as high as 40% on regulated cannabis.32 Local control of cannabis has exacerbated this issue, allowing cities to place taxes on cannabis to fill budgetary shortcomings. Limitations on local control, such as caps on cannabis tax maximums, removing local licensing requirements, and reducing annual fee amounts, would go a long way to addressing the overtaxation problems in the system.

Additionally, as the state reports, excise taxes and fees for cannabis are roughly 77.5% of the wholesale value. Excise taxes and fees for alcohol are about 8.4% of the wholesale value, and excise taxes and fees for tobacco are 29.5% of the wholesale value.”33 The concern here is that cannabis is statutorily mandated to use tax revenues to support anti-drug programs, and the California Highway Patrol, along with other programs. This leaves no additional funding to support the growth and stability of the cannabis industry through tax abatements, loan programs, and capital expenditures incentives to promote hiring and business-to-business (B2B) purchases. Furthermore, the DCC itself is funded through application and regulatory annual fees, which have placed them in a budgetary deficit of $23M for 2024. This model of department funding only incentivizes the department to raise fees as its workload grows, making it harder for firms to obtain licenses due to the higher cost, which creates a steady decline in application/licensing, thereby increasing the department's deficit even more.

Overtaxation and high fees also do not deter the growth of the unregulated market. The Tax Foundation has observed that tax rates exceeding 30% did not prevent the unregulated market in Colorado or Oregon, and California’s rate is 40%. Underlying this entire process is IRS Code 280E, which prohibits cannabis companies from utilizing the federal tax code to offset expenses and costs. For example, most companies can claim a tax deduction for employee costs, purchasing equipment, and virtually any other legitimate business expense. This is the most pressing issue that can only be addressed by the U.S Congress. To make an industry work, the government should focus on reducing the barriers to entry and the barriers to remaining open, like high taxation.

3.4.1 Mandatory Testing & Tracking

When legalization was proposed, one primary concern was whether cannabis products would be safe for commercial consumption. To address these concerns, mandatory testing of product batches is required. Additionally, every seed planted that eventually becomes a flowering plant and then produces an end-user product must be tracked from “seed to sale”. California requires pesticide testing that is more expensive than testing done on most other agricultural products in the state, and tolerance levels are set so low that error rates are high, mandating that entire batches from cultivators are destroyed or remediated, adding higher cost to the final product.34

No other agricultural product in California is as tested as cannabis. Most states generally require internal testing based on a commonly held standard for excluding or determining appropriate levels of certain chemicals or elements. The overregulation of cannabis has made it commonplace for states, and particularly California, to mandate testing at such a high level that it outpaces other industries. A lesson we can learn from Washington state, which had similar strict rules in place, is that when the “strictest testing standards were lifted, [ prices subsequently fell].”35

Additionally, the California Cannabis Track and Trace (CCTT) is the system used to track every seed from growth to sale. This system is a required software-as-a-service (SaaS) system mandated by the government for businesses to utilize, created by a private company based in Florida called METRC. This program has not functioned properly since its initial implementation in the state. Industry experts agreed that the current CCTT system, implemented through METRC, causes high error rates when entering data, companies are incapable of adequately supporting firms with these errors, and API integrations do not work effectively with each other. Some have stated that, “[METRC] drove [operators] away from the regulated market because it's confusing and difficult to use”.36 The DCCs' own consulting experts recommend:37

“The Department continues to dedicate resources to ongoing review and cleaning of CCTT data. Identifying errors and documenting corrections for them continues to improve data accuracy and usefulness… Potential changes to CCTT requirements would lead to reduced diversions of cannabis to the unlicensed market, better information for consumers, and more accurate CCTT data.”

This highlights the inefficiencies in policies that impact the economic activity of regulated cannabis businesses. The government's reports point out that errors in METRC are partially to blame for regulated cannabis fueling the unregulated market. Suppose the goal is to create a functioning industry while making space for smaller social equity operators to exist, and reducing the prevalence of the unregulated market. In that case, these policy decisions have the opposite impact, with overly-high testing standards and a reliance on an error-prone tracking system. California is the birthplace of Silicon Valley, so the expertise to fix these problems is available; there must be a regulatory will to address these concerns.

System of Success

Before we review possible remedies for the problems highlighted in the System of Failure section, we should first define a healthy marketplace. Part of having a viable industry is managing fixed and variable costs. Retailers' variable and fixed costs, such as the rate of utilities, raw materials, and products, can be outside their control. However, there are some steps the state government can take to reduce these costs for retail shops.

Policies to Support Retail Dispensaries with Fixed and Variable Costs

- Develop a low-interest loan program for cannabis operators

- Bring cannabis licensing fees and applications more in line with Alcohol

- Prohibit localities from requiring any additional licensing, outside of general business licensing practices for the city

- Cap or prohibit the amount cities can charge in a cannabis tax between 0% and 0.025%

- Reduce the state excise tax to between 0% and 5%

- Remove or reissue the CCTT program to reduce support businesses frustrated with the program, entice operators to staff, and reduce errors that contribute to the unregulated illicit market

4.1 The High Cost of Taxes

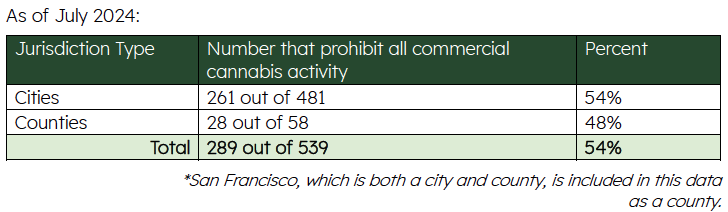

The California cannabis market faces several challenges, one of which is being undercut by the unregulated marketplace. As we move towards policy recommendations, the impact of taxes and regulations on the ability of retailers to maximize their profits in the industry is a better criterion for measuring the health and stability of the cannabis industry in California. The current equilibrium price per ounce of legal cannabis is $258.88 (P1), while the current unregulated price is $175.00 (P2). Due to taxes and regulations, the cost of transitioning from unregulated to legal markets has increased by 32%. Any intervention should reduce this gap, allowing retailers to make operating in the legalized market more profitable than in the unregulated one.38

4.2 Criteria for Success

Any effective policy criteria should understand the values embedded in the development of the current system and how it needs to be supplanted with a new system. The criteria selected that provide the framework for my policy recommendations include:

- Equity & effectiveness: Increases the number of successful social equity businesses as a state goal.

- California’s stated goal is to support and increase the viability of equity operators, so all policy recommendations must not negatively impact this segment of the cannabis economy.

- Harm reduction: Reduce unintended consequences to currently operating businesses.

- Because the industry is already suffering from harmful policies, it is important that we reverse these effects at best and do not increase their influence at worst.

- Generate Economic Activity: Lowers the cost of market entry barriers.

- As the evidence demonstrates, sales are flat, if not down, in California, and the wholesale price is currently not optimal for retailers. Recommended policies should increase sales and activities that increase retailers' bottom lines.

- Feasibility: Political and bureaucratic implementation.

- What is politically possible is generally a subjective term. Because of this, I will push the boundaries of what is usually considered possible, assuming that a motivated executive branch will move bills in the legislature and confront some special interest.

4.3 Policy Recommendations: Successful Scenarios

The health of the cannabis retailer is paramount to the longevity and viability of the California cannabis industry. Policy recommendations that are siloed and implemented individually often do not address all of the core concerns of the specific problem. The recommendations I am presenting are best done in conjunction with each other, and the level of alterations to existing policies will determine the overall effect on the marketplace.

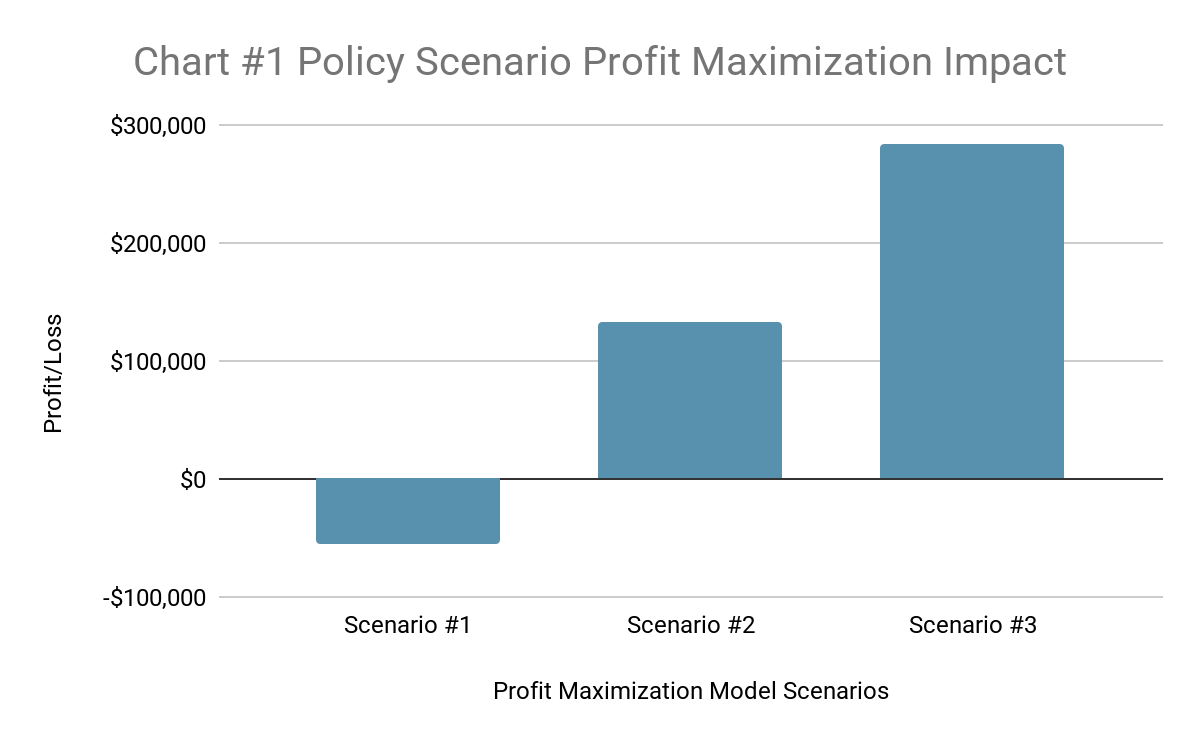

To illustrate this, I will present three scenarios utilizing my profit maximization model to provide the state with the current case, base case, and best case possibilities. The chart below will highlight the exogenous parameters(red) outside the state's control that influence the market. I will note the implementable policy variables (blue), where variations in these categories can dramatically change market dynamics. Also, after Appendix 1, I have included a bar chart demonstrating each policy scenario's economic impact on an operator's financial decision to open a retail dispensary by highlighting their estimated profits and losses. Optimally, the state would implement scenario #3. However, scenario #2 is a more realistic and effective policy framework for improving cannabis in the state.

APPENDIX 1

Retail Cannabis Scenario Parameter Assumptions

Policy Variations

Exogenous Parameters

Annual Fixed Cost

Cost of Capital

Variable Cost of ⅛ Flower

State Licensing fees/app

$13,500

Principle Startup Cost

$1,000,000

Wholesale Flower price per unit

$13

Local Licensing fees/app

$10,000

Interest Rate

20%

State Sales Tax

0.075%

Staffing

$260,000

Term of Loan

60 Months (5 yrs)

State Cannabis Excise Tax

0.15%

Security

$100,000

Annual Cost of Capital

$26,500

Local Sales Tax (SF)

0.08625%

Community Improvement

$10,000

Local Cannabis Tax (SF)

0.25%

Professional (Lawyers, Accountants)

$20,000

Total Variable Cost per unit

$17.37

Tech hardware and software

$50,000

Retail Price

$32

General Commercial Insurance

$6,000

Operating Margins

14.6%

Worker Comp

$8,400

Annual Quantity Sold

70,000

Utilities

$24,000

Total Net Revenues

$1,024,013

POS System

$2,400

Rent

$180,000

CapX39

$50,000

Annual Fixed Cost

$1,080,000

Annual Profit/Loss

$(55,000)

4.4 Scenario #1 Current Level: Let Present Trends Persist

The general parameter assumptions are depicted in Appendix 1. Chart #1 illustrates the impact of all three scenarios. They are based on market analysis, expert interviews, and government reports. Within Annual Fixed Costs, the government's primary role is the cost of licensing and fees at the state and local level, with current levels higher than its substitution counterpart, alcohol. Furthermore, the state utilizes these fees to fund the department, and as the industry contracts, the department's budget shrinks, limiting its ability to address market concerns. Currently, the state does not offer significant financing options for cannabis retailers, leaving them at the whims of the market. Because the California marketplace was initially inundated with capital resources, and since those sources have decreased exponentially, operators are limited to banks with extremely high interest rates. Lastly, letting these trends persist will also not meet the stated criteria. Current operators, social equity, and non-social equity will continue to be harmed financially, which does not lower the market barriers. However, it is politically feasible and implementable because it requires the government to do nothing.

4.4.1 Scenario #1 Current Level: Addressing the Outcomes & Tradeoffs

Policies have tradeoffs that must be considered when deciding what to change. There are clear benefits and serious consequences for letting the present trends persist. Primarily, we can expect a continued contraction in the cannabis industry, especially in the retail sector, where the unregulated market and local jurisdictions are eating away at their margins and ability to gain market share. As some experts noted, the unregulated market is a boon for cultivators and a knife in the back for retailers. Also, the DCC will continue struggling with its budget deficits as fewer entrepreneurs decide to open up shop in California. At the same time, the cost of capital remains oppressively high and out of reach for most. Localities and the state will see a plateauing of cannabis revenues, with a likely outcome of enticing more consumers to move to the unregulated market if prices increase in the regulated space. However, one factor that could rescue the entire state industry from these effects is federal legalization. California’s market would instantly become valuable for exporters of raw materials like dried flower, the main ingredient for all THC products. If that were to occur, it would also reopen basic banking and financial options for operators, providing them with lower interest rates and more capital.

4.5 Scenario #2 Base Level: Policy Recommendations

For this scenario, I will list an optimal set of policy changes that, when collectively implemented, will positively influence the market to meet the state's economic goals.

Policy Changes:

- Restrict local taxation to 0.005% to 0.015%

- Reduce the state excise to between 0.025% and 0.05%

- This change will impact state revenues, so a scheduled decrease over time is recommended

- The state will also need to change how it allocates tax revenues from cannabis away from California Highway Patrol and drug education programs to address additional budgetary constraints

- Create a loan and financing program, either managed by the state or through a public/private partnership, to increase financing options and reduce interest rates to 0.09% to 0.15%, which is still higher than the current industry average for business loans of 0.06% to 0.12$

- Restrict state application fees and licensing to between $2,000 and $5,000 in total cost to a new applicant, and for annualized fees

- Changing the fee structure will impact the budget for the DCC; to address this, their budget should be linked to the industry's growth. Allocating 2.5%-5% of the total tax revenues collected each year would generate an estimated $50M covering the current budget deficit, while incentivizing efficient market management from the DCC.

- Additionally, restricting any cannabis specific local licensing requirements will negatively impact cities and counties while positively affecting operators who no longer have to manage dual licensing requirements.

- Restrict local application fees to $500 to $2,000

- Reallocate funds for improving and fixing issues with CCTT

- Create a state social equity license supplementing local processes and reducing regulatory burdens for operators

4.5.1 Scenario #2 Base Level: Addressing the Outcomes & Tradeoffs

These policy changes could increase an operator's profit by between $114k and $159k annually. This also meets my criteria, assuming the California executive brand uses its political capital to implement the changes. With these changes, the road to profitability seems much more straightforward for the industry, making entering the market more attractive for potential investors and operators. Also, any increase in consumer surplus will entice unregulated market consumers to move into the regulated market, increasing tax revenues. Consolidating social equity licensing into the state licensing process and improving CCTT METRC would reduce the regulatory burden on cities and operators.

Some potential tradeoffs include a decrease in revenues for state and local governments initially, with a potential increase as consumers enter the legalized market because of lower prices and a more competitive environment, reducing the estimated $2B in unregulated activity. There will be pushback from special interest groups like the California League of Cities and other aligned groups that have traditionally objected to any policies that make cannabis more accessible. Nonetheless, this scenario is the most practical and effective way to rescue California cannabis retailers.

4.6. Scenario #3 Best Level: Policy Recommendations

This best-case scenario presents the most productive policy changes that the state could make, but they are less politically feasible because they drastically impact revenues.

Policy Changes:

- Restrict local taxation to 0.0% to 0.01%

- Reduce the state excise to between 0.0% and 0.03%

- This change will impact state revenues, so a scheduled decrease over time is recommended

- The state will also need to change how it allocates tax revenues from cannabis away from California Highway Patrol and drug education programs to address additional budgetary constraints

- Create a loan and financing program, either managed by the state or through a public/private partnership, to increase financing options and reduce interest rates to 0.07% to 0.12%

- Increase loan terms to between 60 and 120 months to extend financing options.

- Restrict state application fees and licensing to between $2,000 and $5,000 in total cost to a new applicant, and for annualized fees.

- Changing the fee structure will impact the DCC's budget; to address this, the budget should be linked to the industry's growth. Allocating 2.5%- 5% of the total tax revenues collected each year would generate an estimated $50M covering the current budget deficit while incentivizing efficient market management from the DCC.

- Additionally, restricting any cannabis specific local licensing requirements will negatively impact cities and counties while positively affecting operators who no longer have to manage dual licensing requirements.

- Require localities to limit the number of retail licenses based on population size to prevent oversaturation.

- Restrict local application fees to $500 to $2,000

- Remove the entire requirements for CCTT

- Create a state social equity license supplementing local processes and reducing regulatory burdens for operators.

4.6.1 Scenario #3 Best Level: Addressing Outcomes & Tradeoffs

By making some minor changes to the base mode, increasing loan terms, and reducing the tax obligation, the model projects firms could earn a maximum profit of $283K, creating even greater benefits for owners. This would also significantly increase the consumer and producer surplus while lowering prices. Additionally, removing the entire CCTT METRC system would be politically difficult because of the promises that every seed and sale would be tracked. However, this system currently does not work, and there is no plan to improve it. The state has succumbed to the sunk cost fallacy by continuing to provide resources to a program that has never worked effectively in the seven-plus years of implementation.

Conclusion

The legalized cannabis industry in California stands at a pivotal juncture. While the state was among the first to transition from prohibition to a regulated market, that system now threatens to collapse under the weight of its policies. Retailers—particularly equity operators—are squeezed between high startup costs, inaccessible capital markets, complex local regulations, and a tax structure that renders legal participation economically irrational.

This white paper has shown that the crisis is not due to market demand or a lack of entrepreneurial interest but rather to a policy ecosystem that overestimates short-term revenue gains while underinvesting in long-term industry viability. Piecemeal reforms are insufficient; what’s needed is a coordinated strategy that lowers regulatory barriers, rationalizes taxation, and invests in retail success, especially for equity operators.

If California wishes to preserve a legal cannabis market that is inclusive, functional, and profitable, bold state-level leadership is required. Policymakers must act urgently to align fiscal policy, regulatory frameworks, and economic development incentives. Failing to do so will erode the state's investment in equity and entrepreneurship and will cede control of the industry back to the unregulated market it sought to replace.

Works Cited

Barcott, Bruce, and Beau Whitney. “Vangst Jobs Report 2024: Positive Growth Returns.” Vangst, 2024.

Black, Lester. “California’s ‘Apple Store of Weed’ Is Close to Collapsing.” SFGATE, February 6, 2023. https://www.sfgate.com/cannabis/article/california-cannabis-medmen-collapsing-17767499.php.

“California’s Pot Economy Is Crashing. What Comes Next?” SFGATE, June 11, 2024. https://www.sfgate.com/cannabis/article/california-cannabis-economy-crash-19492956.php.

California, Department of Cannabis Control-State of. “86% of Californians Who Consume Cannabis Believe It Is Important to Shop Legally.” Department of Cannabis Control. Accessed April 18, 2025. https://cannabis.ca.gov/2024/02/86-of-californians-who-consume-cannabis-believe-it-is-important-to-shop-legally/.

“Cannabis License Summary Report.” Department of Cannabis Control. Accessed April 19, 2025. https://cannabis.ca.gov/resources/data-dashboard/license-report/.

“California Legal Cannabis Market Size & Share Report, 2030.” Accessed April 16, 2025. https://www.grandviewresearch.com/industry-analysis/california-legal-cannabis-market-report.

Cannabis Business Times. “15% of California Cannabis Businesses Default on Taxes as 2025 Hike Comes Knocking,” April 11, 2024. https://www.cannabisbusinesstimes.com/us-states/california/news/15686763/15-of-california-cannabis-businesses-default-on-taxes-as-2025-hike-comes-knocking.

Cannabis Business Times. “Are California Cities Intentionally Misinterpreting Landmark Cannabis Legislation?,” October 16, 2023. https://www.cannabisbusinesstimes.com/us-states/california/news/15687325/are-california-cities-intentionally-misinterpreting-landmark-cannabis-legislation.

Cannabis Conversations - Equity, 2022. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=C37ytmXxuMs.

Choi, Joseph. “Marijuana Rescheduling Runs into Roadblock.” Text. The Hill (blog), January 18, 2025. https://thehill.com/policy/healthcare/5092684-dea-hearing-appeal-marijuana-rescheduling/.

Cohen, Gary. “How Much Is California Dispensary Sales Tax? (Breakdown).” Accessed April 16, 2025. https://www.covasoftware.com/blog/california-cannabis-sales-tax.

“Condition and Health of the Cannabis Industry in California Supplemental Report.” California

Department of Cannabis Control, March 3, 2025. https://cannabis.ca.gov/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2025/03/Report-on-the-Condition-and-Health-of-the-Cannabis-Industry-FNL-03.06.25.pdf.

Corva, Dominic, and Meisel Joshua S., eds. The Routledge Handbook of Post-Prohibition Cannabis Research. Routledge Handbooks. New York London: Routledge, 2022.

ERA Economic. “California Cannabis Market Outlook 2024 Report.” California Department of Cannabis Control, January 1, 2025.

Expert 1. California Cannabis Industry Expert Interview FINSE05. Video Conference Call, March 11, 2025.

Expert 2. California Cannabis Industry Expert Interview FINRES10. Video Conference Call, March 21, 2025.

Expert 3. California Cannabis Industry Expert Interview MSO05. Video Conference Call, March 24, 2025.

Expert 4. California Cannabis Industry Expert Interview FINRES08. Video Conference Call, March 17, 2025.

Expert 5. California Cannabis Industry Expert Interview FINSE02. Video Conference Call, March 24, 2025.

Expert 6. California Cannabis Industry Expert Interview MSO13. Video Conference Call, March 26, 2025.

Higginbotham, Abbey. “‘The Biggest Challenge Is Cash Flow’: Talarya Brands CEO Breaks Down The Struggles Of Non-Retail Cannabis Brands In California.” Benzinga. Accessed April 16, 2025. https://www.benzinga.com/markets/cannabis/24/10/41426841/the-biggest-challenge-is-cash-flow-talarya-brands-ceo-breaks-down-the-struggles-of-non-retail-ca.

“How Do State and Local Cannabis (Marijuana) Taxes Work? | Tax Policy Center.” Accessed April 16, 2025. https://taxpolicycenter.org/briefing-book/how-do-state-and-local-cannabis-marijuana-taxes-work.

Littlejohn, Amber, and Eliana Green. “MCBA National Cannabis Equity Report 2022.” Minority Cannabis Business Association, 2022. https://mjbizdaily.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/National-Cannabis-Equity-Report-1.pdf.

Public Policy Institute of California. “Californians’ Attitudes Toward Marijuana Legalization.” Accessed April 18, 2025. https://www.ppic.org/publication/californians-attitudes-toward-marijuana-legalization/.

Roberts, Chris. “As Marijuana Break-Ins Skyrocket in California, Business Owners Take Action.” MJBizDaily, April 6, 2023. https://mjbizdaily.com/california-cannabis-operators-take-action-as-break-ins-skyrocket/.

Schroyer, John. “First Social Equity Dispensary in U.S. Is Now Closed.” Green Market Report (blog), July 10, 2024. https://www.greenmarketreport.com/first-social-equity-dispensary-in-u-s-is-now-closed/.

“Report: OK, OR and CA Cannabis Companies Could Be Big Winners under Federal Marijuana Legalization.” Green Market Report (blog), March 26, 2025. https://www.greenmarketreport.com/report-ok-or-and-ca-cannabis-companies-could-be-big-winners-under-federal-marijuana-legalization/.

Shah, Athena Chapekis and Sono. “Most Americans Now Live in a Legal Marijuana State – and Most Have at Least One Dispensary in Their County.” Pew Research Center (blog), February 29, 2024. https://www.pewresearch.org/short-reads/2024/02/29/most-americans-now-live-in-a-legal-marijuana-state-and-most-have-at-least-one-dispensary-in-their-county/.

Swift, Jayne. “Are Cannabis Social Equity Programs Truly Equitable?” Gender Policy Report (blog), February 13, 2024. https://genderpolicyreport.umn.edu/are-cannabis-social-equity-programs-truly-equitable/.

Tax Foundation. “Recreational Marijuana Taxes by State, 2025,” April 1, 2025. https://taxfoundation.org/data/all/state/recreational-marijuana-taxes/.