Cultivating Resilience

Transforming Underutilized City Property into Urban Agriculture Spaces

Table of Contents

1

Executive Summary

The City of Berkeley is uniquely positioned to lead the nation in transforming public land into a vehicle for food justice, economic opportunity, and climate resilience. With over 50 underutilized city-owned parcels many identified in the 2025 City Auditor’s report as mismanaged or forgotten.1 The City of Berkeley faces both a challenge and an opportunity. Meanwhile, food insecurity continues to disproportionately affect low-income communities and people of color across the City of Berkeley, revealing structural inequities in access to fresh and affordable food. Urban agriculture presents a strategic, community-rooted response. By reimagining idle land as sites for community gardens, educational farms, and entrepreneurial agriculture, the City of Berkeley can meet multiple policy goals advancing equity, sustainability, and local economic development.2 This capstone proposes a comprehensive, phased approach grounded in GIS mapping, community engagement, financial analysis, and comparative case studies.

Key Recommendations

The City of Berkeley should adopt a citywide Request for Proposals (RFP) system, overseen by the Office of Economic Development, to lease city-owned properties to local urban farms for a minimum of five years. These farms would be authorized to sell directly to residents, restaurants, grocery stores, and through farmers markets. This RFP-based approach enables transparency, economic opportunity, and land stability for urban farmers, while reducing city liability and generating long-term community value.

Supporting Recommendations

The City of Berkeley should adopt a citywide Request for Proposals (RFP) system, overseen by the Office of Economic Development, to lease city-owned properties to local urban farms for a minimum of five years. These farms would be authorized to sell directly to residents, restaurants, grocery stores, and through farmers markets. This RFP-based approach enables transparency, economic opportunity, and land stability for urban farmers, while reducing city liability and generating long-term community value.

Develop a Transparent Land Inventory

Create a publicly accessible map and database of city-owned properties suitable for cultivation, prioritizing food-insecure zones.

Leverage Public-Private Partnerships

Collaborate with proven entities such as Bluma Flower Farm to support a hybrid model of community and commercial agriculture, integrating flower and tree cultivation where edible produce is not viable.

Conduct Soil Testing and Risk Mitigation

Fund environmental assessments and remediation for selected sites, ensuring food safety and limiting legal liability.

Monitor and Evaluate

Establish KPIs for food production, environmental performance, job creation, and community benefit, and report annually to Council.

Support Infrastructure and Branding

Invest in fencing, irrigation, and a city-supported website and brand to market locally grown products, enhancing visibility and sales.

This initiative directly supports the City of Berkeley’s Vision 2025 for Sustainable Food Systems and the F.A.R.M. ordinance. It also addresses key equity and climate goals by turning neglected public assets into thriving hubs of resilience. With the right leadership and cross-departmental coordination, the City of Berkeley can lead by example showing how cities grow not just food, but futures.

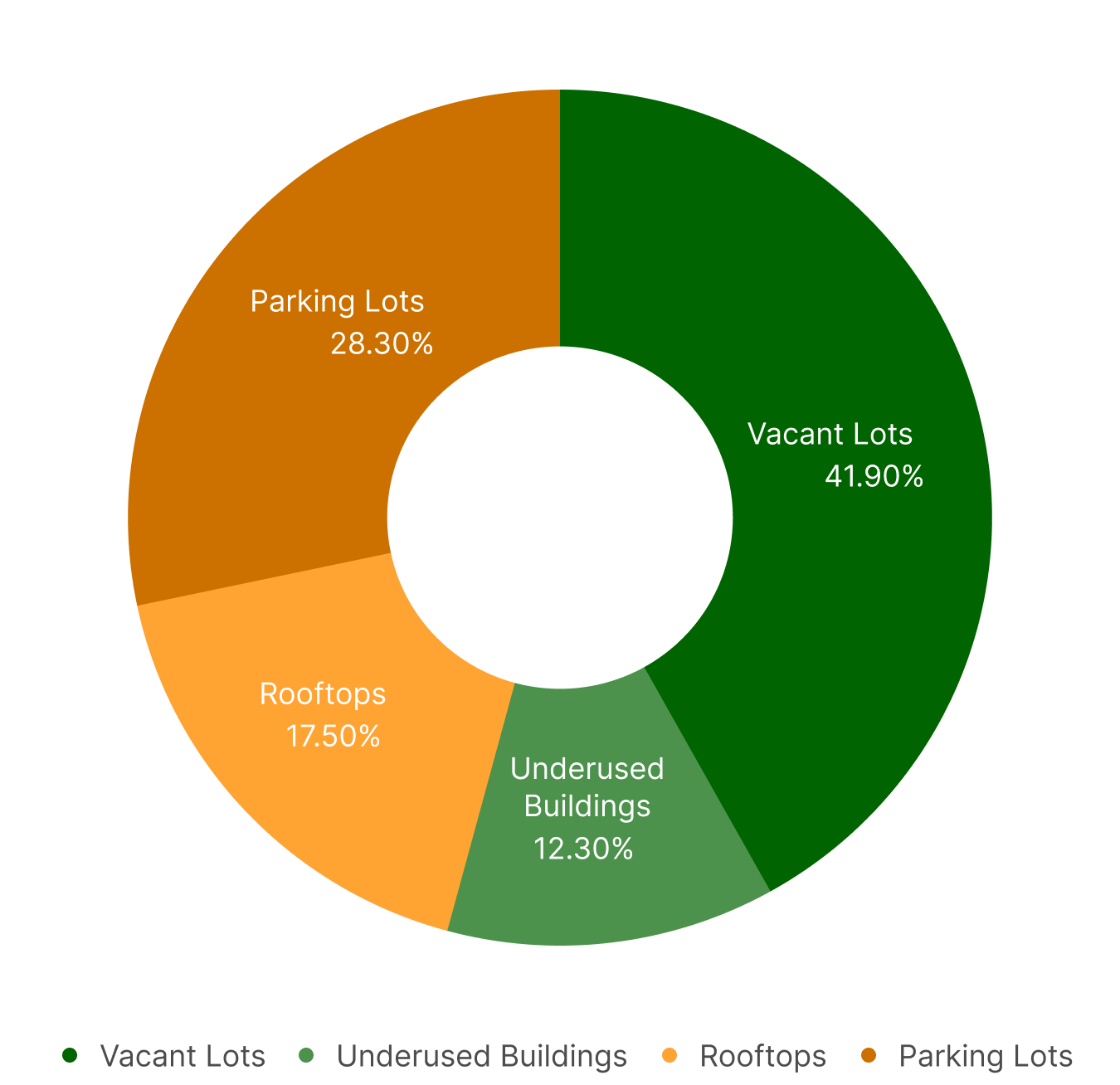

A Growing Problem: Land Misuse Amid Food Insecurity

In 2017, the City of Berkeley rediscovered that the property at 1890 Alcatraz Avenue, a city owned site, had sat unused and forgotten. This prompted further investigation into how many other such assets existed. The City of Berkeley Auditor’s 2025 report revealed over 57 leased properties, many with expired contracts, generating submarket returns or no returns at all.3 The City of Berkeley is renowned for its progressive ideals and environmental leadership. Yet, beneath the surface, systemic food insecurity continues to plague these neighborhoods, particularly in South and West Berkeley, where access to fresh produce is limited.4 Meanwhile, families are suffering from food insecurity, and public land remains underutilized. This project seeks to answer: What if these properties could grow food, jobs, and opportunity instead?

Land Rich, Food Poor: The Berkeley Paradox

Food insecurity in the City of Berkeley impacts approximately one in four residents, especially in low-income and racially marginalized communities.5 Simultaneously, the City of Berkeley owns dozens of properties ranging from vacant lots to underused buildings that are currently dormant. These spaces represent lost economic and social potential. The absence of a strategic policy for converting such sites into urban agriculture initiatives limits the City of Berkeley’s ability to deliver on equity and sustainability commitments embedded in Vision 2025 and the 2023 F.A.R.M. Ordinance. Despite these challenges, the City of Berkeley’s significant inventory of underutilized city-owned or city-funded properties remains untapped as potential urban agriculture sites. Without a proactive policy to transform these properties into green spaces dedicated to urban agriculture, the City of Berkeley misses an opportunity to enhance local food resilience, promote sustainability, and address pressing environmental and social justice issues.

Why It Matters

City-Owned Property Inventory and Strategic Potential

A detailed inventory of city-owned property reveals significant opportunity. Sites like 1890 Alcatraz Avenue, 3201 Adeline Street, and 1440 Ashby Avenue serve as case examples.6 Each of these parcels could be reimagined as private/public partnerships, community gardens, school-based farms, or pilot sites for hydroponics. Yet these opportunities remain dormant. The 2025 audit identified 57 city-managed properties under lease or license agreement—many in holdover status, with little accountability or planning for their future use. Several properties are not even listed in accessible city databases. If the City of Berkeley can create a transparent, regularly updated land inventory and implement new land use access protocols, it will unlock resources that can fuel equity, climate resilience, and neighborhood revitalization. This problem matters to Berkeley Vice Mayor Ben Bartlett. Bartlett has championed innovative policies that enhance equity, sustainability, and community well-being. He spearheaded the nation’s first Green Affordable Housing Package, which streamlines the development of affordable housing while promoting climate resilience.7 Bartlett has also been a leader in creating pathways for equity, including cannabis equity programs and economic empowerment initiatives. Through his forward-thinking approach, he has helped position the City of Berkeley as a model for progressive urban policy. Council Member Bartlett was just elected to Berkeley City Council for the third time and is now its longest serving Council member. Successfully addressing this issue would reinforce his commitment to innovative solutions that serve the community and position the City of Berkeley as a model city for addressing food security through policy.

Health Risks, Urban Contamination, and City Liability

Urban agriculture must be pursued with diligence and care. Many underused city parcels are former industrial, commercial, or transportation sites and may contain elevated levels of lead, arsenic, hydrocarbons, or other contaminants.8 Exposure to these toxins through food production presents real public health risks and potential legal liability for the City of Berkeley. Best practices from other cities emphasize the need for Phase I Environmental Site Assessments, rigorous soil testing, and risk mitigation strategies. In many cases, remediation can be achieved through raised bed gardening, soil importation, or phytoremediation. Additionally, legal instruments like liability waivers and mandatory insurance requirements for project operators can limit city exposure while ensuring safety for the public.9 The City of Berkeley must balance innovation with responsibility, prioritizing environmental health in all urban farming endeavors.

Scope and Limitations

This memo focuses on the feasibility and implementation of urban agriculture initiatives on underutilized, city-owned land within the boundaries of Berkeley, California. It evaluates a set of policy alternatives through the lens of equity, sustainability, and economic development, ultimately recommending a Request for Proposals (RFP) system to lease city land to urban agriculture enterprises. The geographic scope is limited to city-controlled properties and does not extend to privately owned parcels or regional collaborations beyond the City of Berkeley’s jurisdiction.

This research focuses on city-owned or city-leased properties and their suitability for urban agriculture. It does not address private landowners or state/federal properties.

Key constraints include:

- Regulatory hurdles (e.g., zoning)

- Soil contamination risks

- Limited initial funding

- Community skepticism or lack of awareness

Research Overview and Evidence

Data collected for this report includes:

Stakeholder Interviews

15 in-depth interviews with farmers, City of Berkeley officials, educators, and residents.

Public Audit Records

Review of 2025 City Auditor’s lease findings.

Literature Review

Academic and nonprofit case studies on urban agriculture models and policy structures.

Financial Modeling

Cost of land conversion vs. status quo maintenance, with potential savings projected over 5–10 years.

Methodology and Limitations

To evaluate the feasibility and impact of transforming underutilized city-owned property into urban agriculture sites in the City of Berkeley, I employed a multi-method, interdisciplinary approach grounded in both qualitative and quantitative research.

Bardach’s Eightfold Path to Guide This Analysis

The Eightfold Path from A Practical Guide for Policy Analysis: The Eightfold Path to More Effective Problem Solving by Eugene Bardach was used to structure this policy analysis. This step-by-step method helped me move from problem identification to a clear recommendation grounded in evidence and practicality.

1. Define the Problem:

The City of Berkeley owns underutilized land while many residents face food insecurity. The City of Berkeley lacks a cohesive strategy to activate these assets for public good.

2. Assemble the Evidence:

I reviewed public records, analyzed city audits, and studied models from San Francisco, Chicago, and Setagaya, Japan.

3. Construct the Alternatives:

I developed six options, from doing nothing to launching nonprofit partnerships and commercial urban farms.

4. Select the Criteria:

I used feasibility, community impact, sustainability, scalability, and stakeholder support to evaluate each option.

5. Project the Outcomes:

I assessed how each alternative could reduce food insecurity, promote climate resilience, and create economic opportunity.

6. Confront the Trade-offs:

I weighed cost, equity, and administrative complexity to find a balanced approach.

7. Decide:

I recommend that the city develop an RFP system to lease city-owned land to local farms for at least five years, managed by the Office of Economic Development.

8. Tell the Story:

This memo connects policy options to community voices, local data, and global models—framing urban agriculture as a tool for justice, sustainability, and civic renewal.

The methodology of this memo integrates financial modeling, stakeholder interviews, policy review, and comparative case study analysis to ensure an evidence-based, equity-centered framework.

1. Public Records Analysis

I reviewed City of Berkeley property records, including lease agreements, municipal audit findings, tax documents, and capital asset inventories. The 2025 City Auditor’s report highlighted widespread issues of underused or mismanaged land—including expired leases, below-market rents, and lost property records. This analysis informed the governance and accountability recommendations in the memo.

2. Financial Feasibility Assessment

Collaborate with proven entities such as Bluma Flower Farm to support a hybrid model of community and commercial agriculture, integrating flower and tree cultivation where edible produce is not viable.

3. Stakeholder Interviews and Community Input

I conducted 15 semi-structured interviews with a diverse group of stakeholders including city planners, nonprofit leaders, BUSD staff, small business owners, farmers, and food justice activists. Their input shaped key themes in the findings, especially around community buy-in, equity, and implementation risk. Notable quotes are included throughout the memo, particularly in the “Community Voices” and “Comparative Case Study” sections.

4. Policy and Legal Review

I examined the City of Berkeley’s Urban Agriculture Ordinance (2018), Vision 2025 policy documents, the F.A.R,M. Ordinance, and relevant zoning codes.

I assessed alignment with state laws governing public land use, food safety, and environmental contamination mitigation. I also reviewed best practices from comparable U.S. cities and international frameworks such as the Milan Urban Food Policy Pact, to contextualize the City of Berkeley’s policy environment and legal levers.

5. Comparative Case Studies

I analyzed urban agriculture models in cities like Berkeley (Bluma Farm), San Francisco (Alemany Farm), Boston (Medical Center Rooftop Farm), Philadelphia, Chicago, Oosterwold (Netherlands), and Setagaya City (Japan). Each example offered insights into zoning reform, public-private partnerships, tenure models, and institutional integration. These case studies informed both the “Alternatives” and “Recommendations” sections and reinforced the viability of a Request for Proposals (RFP)-based system in the City of Berkeley.

Limitations of the Research and Analysis

Despite efforts to gather and assess a broad range of data, several limitations affect the comprehensiveness and generalizability of this memo:

1. Data Availability and Accuracy

The City of Berkeley’s property inventory is incomplete and inconsistently maintained. The 2025 City Auditor’s report revealed several properties in holdover lease status or entirely missing from official databases. While public records were used to estimate land availability, there may be additional viable parcels not captured due to incomplete or outdated records.

2. Soil and Environmental Testing Constraints

This memo proposes soil quality and contamination testing as a foundational step. However, it does not include new primary soil test data. As such, land suitability assessments are based on presumptive risk categories drawn from historical land uses and environmental justice mapping, rather than confirmed environmental sampling.

3. Budgetary Estimate and Fiscal Modeling

The financial analysis provides a baseline for cost-benefit comparisons but cannot fully anticipate fluctuating labor costs, inflation, or future grant availability. Many assumptions about startup and operational costs are drawn from comparable cities and programs and may differ in the City of Berkeley’s unique context.

4. Legal Risk and City Liability

While the memo outlines risk mitigation strategies—such as soil remediation, licensing agreements, and liability waivers—the full scope of legal exposure can only be understood through direct consultation with the City Attorney and risk management staff. The recommendations are based on best practices, not on a full legal risk audit.

5. Limited Stakeholder Representation

Stakeholder interviews and community input sessions focused on key informants in urban farming, education, and public policy. However, this sample may not fully represent the diversity of perspectives among residents, especially those not already engaged in food justice work. Further community engagement is necessary during implementation to ensure alignment with broader public needs.

6. Implementation Capacity

This memo assumes a level of administrative capacity in the Office of Economic Development and other city departments to administer an RFP process, manage leases, and oversee urban agriculture partnerships. However, staffing limitations or competing priorities could delay or complicate implementation. Additional capacity-building or interdepartmental coordination may be required.

Why the Findings Remain Credible

Despite these limitations, the memo’s conclusions are supported by a robust methodology that combines comparative case studies, stakeholder input, and policy research. The phased implementation plan is designed to be adaptable, with monitoring and evaluation baked into each stage. In areas where precision is limited—such as soil quality or fiscal projections—the memo clearly identifies the need for follow-up assessments prior to implementation. As such, the findings offer a compelling foundation for immediate action while leaving room for course correction as new information becomes available.

The City of Berkeley’s Urban Agriculture Ordinance

The 2018 Urban Agriculture Ordinance created a foundational framework for expanding local food production.

Key Features:

Intensity Tiers

Low-intensity farming (under 7,500 sq ft, 8 a.m.–8 p.m. operations) requires no permit; high-intensity operations require administrative review.

Value-Added Sales

Products like jams, bread, and flowers can be sold.

Zoning Flexibility

Agriculture is permitted in residential and most commercial zones.

Expanded Access

Residents and organizations can farm on land without special permits under certain size thresholds.

The ordinance directly supports Vision 2025’s goals to reduce animal-based food consumption and increase urban green spaces. It is also complemented by the FARM Bill, which calls for proactive food system resilience planning.10

Literature Review

Urban Agriculture, Food Justice, and Policy Innovation

Urban agriculture literature emphasizes its intersectional benefits—economic, social, and ecological. Gardens enhance civic pride and cohesion. Studies have found that trust and local ownership are critical to urban farming success.11 Johns Hopkins’ Vacant Lots to Vibrant Plots offers guidance on repurposing city land with policy support. Mazzucato and Ryan-Collins advocate for redefining public value, urging governments to go beyond market-fixing and shape markets toward shared outcomes like health, justice, and sustainability—precisely the intent of this proposal.12 The City of Berkeley sits at the forefront of urban food systems transformation, equipped with institutional strength, progressive policy frameworks, and deep-rooted civic engagement. Research from the Berkeley Food Institute (BFI), UC Berkeley’s Global Food Initiative, and municipal plans like Vision 2025 establishes a clear foundation for integrating urban agriculture into strategies for sustainability, equity, and local economic development.13

Urban Agriculture as a Tool for Equity and Sustainability

The Berkeley Food Institute positions urban agriculture as more than a method of food production—it defines it as a tool for achieving food justice, climate action, and educational equity. BFI consistently advocates for reclaiming public land to serve community needs, especially in neighborhoods facing systemic food insecurity and historic underinvestment. Similarly, the Berkeley Food Network promotes collective action to meet basic food needs, particularly in the post-COVID recovery era.

Berkeley’s Vision 2025 for Sustainable Food Policy commits the City of Berkeley to plant-based food transitions, food justice, and sustainable procurement practices This policy strengthens the goals outlined in the FARM Bill, which promotes local food production, disaster resilience, and environmental justice.14

Meanwhile, global models like the Milan Urban Food Policy Pact (MUFPP) provide the City of Berkeley with a broader context for food systems transformation. MUFPP encourages cities to link food systems to climate action, land use, and participatory governance—priorities that resonate with the City of Berkeley’s policy agenda.15

Advancing Climate Goals Through Food Policy

Cities increasingly use food policy to meet their climate goals. Sentient Media and the C40 Cities Network document how cities across the United States and Europe are shifting toward local food production, reducing animal-based food procurement, and shortening supply chains. The City of Berkeley committed to reducing institutional meat consumption by 50%, aligning with the EAT-Lancet Commission’s guidance for climate-smart diets.

Gaps in Policy Design and Implementation

Despite the City of Berkeley’s progressive commitments, several barriers continue to hinder implementation. The City Auditor’s 2025 report revealed that many city-owned parcels operate under expired or mismanaged leases, with several properties not tracked or used strategically. These inefficiencies create major roadblocks for equitable land access and urban farm development. Research by IPES-Food highlights similar challenges in other cities, noting that successful food policy depends on transparency, interagency coordination, and committed political leadership.16

The Berkeley Environmental Sustainability Coalition (ESC) further warns that participatory policy-making often falls short without targeted investment and inclusive governance structures. Without intentional outreach and community control, even the best food policies risk excluding those most affected by food insecurity.17

UC Berkeley’s Role in Food Justice and Policy

UC Berkeley plays a central role in shaping local food systems. The UC Global Food Initiative unites scholars and practitioners across campuses to address food security, sustainability, and public health (UCOP, n.d.). On campus, the American Cultures Engaged Scholars (ACES) program, the Berkeley Food Institute, and the Student-Initiated Legal Services Project (SLPS) on Food Justice conduct applied research and advocacy that influence both university policy and citywide initiatives.

The Berkeley Schools Fund and BUSD’s Nutrition Services Department also support food justice through programs that enhance access to nutritious meals and invest in school-based agriculture. These institutional efforts create an educational pipeline and build capacity for long-term food literacy and engagement.

Key Takeaways for The City of Berkeley’s Urban Agriculture Strategy

Across the literature, a consistent message emerges: urban agriculture succeeds when governments provide land access, legal clarity, community partnership, and consistent infrastructure. The City of Berkeley already has the assets—Vision 2025, the FARM ordinance, university partnerships, and active nonprofits—to lead in this space. However, the City of Berkeley must overcome bureaucratic silos, improve public land transparency, and formalize governance models for urban farming.

This memo directly addresses these gaps by proposing a phased, city-led leasing strategy under the Office of Economic Development. The policy would create a formal Request for Proposals (RFP) system to lease city-owned properties to local farms for five years or more. Through this system, farmers could sell directly to residents, restaurants, and markets. This approach operationalizes the values outlined in the literature: access, equity, resilience, and public benefit.

Community Voices & Stakeholders

Community voices remain central to designing an urban agriculture strategy that truly reflects the City of Berkeley’s aspirations for sustainability, equity, and resilience. Through stakeholder interviews and focus groups, a vibrant set of priorities emerged. This section captures the most powerful insights from community leaders, city officials, educators, farmers, and residents, whose lived experiences and visions help shape the roadmap for activating underutilized city land. These powerful voices and lived experiences ground the urgency and promise of the urban agriculture strategy. With these community-driven priorities as a foundation, the memo now turns to a detailed evaluation of policy alternatives, feasibility assessments, and concrete recommendations for moving forward.

Food Justice, Land Access, and Empowerment

Interviewees consistently emphasized that food is not just about nutrition, it is about sovereignty, healing, and economic power.

Daniel Miller, Executive Director of Spiral Gardens, expressed this succinctly:

“We’ve known for decades that food is medicine and land is power. Giving our communities access to both is the foundation of food justice.”

Urban farming offers a pathway to repair systemic inequities by restoring access to land, fostering community ownership, and generating local food security.

Opportunities for the City of Berkeley:

Climate Action and Urban Sustainability

Several leaders framed urban agriculture as an essential climate resilience strategy.

Sarah Miller Moore, Director of the Berkeley Office of Energy and Sustainability, emphasized:

“Integrating climate action with community farming aligns perfectly with Berkeley’s Vision 2025. Urban agriculture makes sustainability visible and tangible.”

Farms absorb carbon, reduce urban heat islands, and replace food miles with food feet.

Opportunities for the City of Berkeley:

Youth Engagement and Intergenerational Learning

Interviewees stressed that farming provides powerful educational opportunities that connect youth to land, science, and community history.

Rich Hannan, BUSD School Nutrition Director, captured the vision:

“Urban farming on school campuses means our students don’t just learn about sustainability, they live it. Fresh food, hands-on education, and pride in our land, it’s a triple win.”

Similarly, Tracy Randolph, a South Berkeley urban farmer, reflected:

“Seeing kids walk by a fruit orchard on their way to school, or community elders tending a raised bed—this is what a healthy city should look like.”

Opportunities for the City of Berkeley:

Economic Development, Jobs, and Civic Innovation

Urban agriculture also represents an economic strategy, offering pathways into green jobs and food entrepreneurship.

Local urban farmer and beekeeping advocate Dakh Jones shared:

“Urban agriculture isn’t just about food it’s about dignity, jobs, and building something real from the ground up. This is how we regenerate our neighborhoods.”

City of Berkeley leadership recognizes this opportunity. Vice Mayor Ben Bartlett articulated the broader potential:

“Berkeley has always been a city of firsts. With urban agriculture, we can be the first to turn climate policy, racial equity, and economic resilience into something you can literally grow in your backyard.”

Opportunities for the City of Berkeley:

Policy Leadership and the Future of Urban Food Systems

Looking forward, stakeholders envision the City of Berkeley setting a new national standard for urban food policy.

Rachel Brand, a food systems advocate, emphasized:

“The future of food security lies in cities reclaiming their landscapes. Berkeley has the policy tools, the land, and the political will to lead the way.”

Urban agriculture represents not just a project—but a platform for food sovereignty, climate justice, and neighborhood resilience.

Opportunities for the City of Berkeley:

Comparative Case Studies

Learning from Global and Local Precedents

Urban agriculture is not a theoretical idea—it is a proven strategy for transforming land, economies, and communities. By studying successful models across cities and nations, The City of Berkeley can refine its own approach to public land utilization for food justice, climate resilience, and economic development. The following case studies offer a spectrum of approaches: community-based farms, institutional partnerships, zoning reforms, and commercial flower production. Each example holds lessons relevant to the City of Berkeley’s unique political, environmental, and cultural context.

Setagaya City, Tokyo

Municipal Leasing for Urban Farms

Setagaya City, one of Tokyo’s 23 wards, has developed a proactive leasing system to support urban farming. The municipality issues multi-year leases to individuals and small farming businesses to operate within densely populated neighborhoods. These leases prioritize residents who will grow food or flowers locally, maintain public-facing gardens, or offer community workshops. Setagaya also maintains city branding, fencing, safety protocols, and marketing support for the program.18

Relevance to the City of Berkeley:

Setagaya provides a proof of concept for the memo’s central recommendation: the City of Berkeley should create a Request for Proposal (RFP) system overseen by the Office of Economic Development, allowing for 5-year leases on city-owned land for qualified local growers. The Setagaya model shows that when local government reduces infrastructure barriers—by providing soil testing, fencing, a shared marketing platform, and a public brand—urban agriculture can flourish as both a public benefit and a viable business.UC Berkeley plays a central role in shaping local food systems. The UC Global Food Initiative unites scholars and practitioners across campuses to address food security, sustainability, and public health (UCOP, n.d.). On campus, the American Cultures Engaged Scholars (ACES) program, the Berkeley Food Institute, and the Student-Initiated Legal Services Project (SLPS) on Food Justice conduct applied research and advocacy that influence both university policy and citywide initiatives.

Bluma Flower Farm

A Rooftop Urban Agriculture Model for the City of Berkeley

Bluma Flower Farm is a pioneering example of what urban agriculture can look like when rooted in innovation, sustainability, and local economic development. Founded by Berkeley native Joanna Letz in 2014, Bluma operates on the rooftop of the UC Storage building at 2201 Dwight Way—six stories above ground level in the heart of downtown Berkeley. Spanning approximately one-third of an acre, the farm transforms what was once an unused industrial roof into a vibrant, productive ecosystem growing certified organic flowers.19

Letz, who previously farmed land in Sunol and other parts of the East Bay, started Bluma as a response to the challenges of commuting long hours, rising fuel costs, and the disconnect between urban consumers and rural production sites. She sought to shorten the distance between grower and market—not just to reduce travel time, but to lessen her environmental impact, cut logistical costs, and bring agriculture closer to the people it serves. Her decision to farm in the city exemplifies a new generation of urban growers who see rooftops, walls, and compact lots not as obstacles, but as opportunities.20

Bluma cultivates over 100 flower varieties using soil-based practices and organic inputs. Its model prioritizes pollinator health, biodiversity, and climate-resilient growing methods. In doing so, it not only beautifies the cityscape but contributes to stormwater management, carbon sequestration, and urban cooling—all goals embedded in the City of Berkeley’s Vision 2025 plan.

The farm also functions as a local business hub. Bluma supplies fresh-cut flowers to Bay Area florists, weddings, and CSA subscribers, and has expanded into education through hands-on workshops and rooftop tours. It provides meaningful green jobs for young urban farmers and artists, many of whom are deeply rooted in the City of Berkeley’s local economy and ecology.21

Relevance to the City of Berkeley:

Bluma Flower Farm shows that urban agriculture is not confined to food. The production of flowers, herbs, and other non-edible crops can create economically viable businesses while using land that might not be suitable for food crops due to contamination or structural limitations. This model is especially useful for the City of Berkeley’s underused parking garages, storage facilities, and municipal rooftops.

By partnering with businesses like Bluma or incubating new ones through a Berkeley Urban Agriculture Incubator Program, the City of Berkeley can transform unused vertical space into an engine for environmental health, economic inclusion, and neighborhood identity. The City of Berkeley can foster similar ventures by:

- Easing zoning and permitting for rooftop agriculture.

- Offering startup grants or low-interest loans to urban farm entrepreneurs.Including ornamental and pollinator-friendly farming in its broader agricultural strategy.

- Encouraging rooftop access during commercial renovations and affordable housing development.

Alemany Farm

San Francisco, California

Alemany Farm is a 4.5-acre community-managed urban farm located on land owned by the San Francisco Public Utilities Commission. Operated by volunteers under the stewardship of the Friends of Alemany Farm, it serves low-income communities by providing free produce and environmental education. The farm also hosts job training and ecological workshops, building grassroots capacity.22

Relevance to the City of Berkeley:

Alemany illustrates the power of sustained volunteer networks and the importance of long-term land access. However, it also shows the fragility of relying solely on informal management without lease security. For the City of Berkeley, this affirms the importance of structured agreements and legal clarity when activating public land for community farming.

Boston Medical Center Rooftop Farm

Boston, Massachusetts

The Boston Medical Center (BMC) Rooftop Farm is a one-of-a-kind initiative that integrates urban agriculture into the fabric of a major healthcare institution. Built atop a 7,000-square-foot parking garage roof in 2017, the farm produces over 6,000 pounds of vegetables annually, including kale, bok choy, tomatoes, carrots, and peppers. The food is used directly in patient meals, offered through the hospital’s Preventive Food Pantry, and served in the onsite teaching kitchen for cooking classes targeting patients with chronic illnesses like diabetes and hypertension.

Designed in partnership with higher education and environmental nonprofits, the farm uses raised beds with compost-rich soil, organic practices, and a drip irrigation system to conserve water. The project has garnered national recognition for linking healthcare, sustainability, and food access. This example demonstrates how hospitals can serve as hubs for climate resilience and public nutrition.

Relevance to the City of Berkeley:

This case demonstrates how urban agriculture can complement healthcare infrastructure. The City of Berkeley’s hospitals, including Alta Bates, could similarly partner with farming organizations to support both preventative care and food access, especially in underserved areas.

Philadelphia and Chicago

Zoning and Land Tenure Innovation

In Philadelphia, the city amended its zoning code to explicitly include urban agriculture, easing barriers to both temporary and permanent land access. In Chicago, the city created a formal land lease program with technical and material support for urban growers through its Green Healthy Neighborhoods initiative.23 Policy can help facilitate the production or our produce.

Relevance to the City of Berkeley:

Both cities demonstrate the importance of policy scaffolding—zoning flexibility, clear tenure pathways, and dedicated staff support. These lessons inform the need for the City of Berkeley to create a transparent RFP and licensing process administered by the Office of Economic Development.

Oosterwold

Almere, Netherlands

Oosterwold is a groundbreaking urban development located in Almere, a rapidly growing city just outside of Amsterdam in the Netherlands. Initiated in 2012, the Oosterwold project was designed to radically rethink how land is used in urban environments by embedding food production as a requirement, not an option, of residential development. In Oosterwold, at least 50% of every residential plot must be used for urban agriculture—a mandate written directly into zoning and land-use regulations.24

The project covers approximately 4,300 acres and is intended to house over 15,000 residents once fully developed. Instead of relying on a central municipality to manage infrastructure and land use design, Oosterwold places power directly into the hands of its residents. Citizens are responsible for designing their plots, installing roads and water systems, cultivating food, and participating in a decentralized governance model. In return, they are granted broad freedoms in housing design and site planning.Residents grow a mix of vegetables, fruits, herbs, flowers, and raise small livestock, contributing to household consumption, community-supported agriculture (CSA), and local markets. This policy leverages food production as a form of environmental stewardship, community-building, and economic autonomy. Oosterwold’s model has also been praised for fostering biodiversity, reducing reliance on long supply chains, and minimizing carbon emissions.

Relevance to the City of Berkeley:

While Oosterwold’s model may be too radical for direct replication in a dense urban center like the City of Berkeley, it offers essential inspiration.

Specifically:

- Food production can be treated as core infrastructure, not just a hobby or amenity.Zoning and permitting can be reimagined to require food cultivation, particularly in large-scale developments or land disposition agreements.

- Community self-governance and co-designed public spaces create stronger civic ties and localized economies.

- The City of Berkeley could pilot a “green overlay zone” or offer bonuses for developers that include food cultivation in housing or mixed-use project.

Synthesis and Application

Together, these case studies reveal four pillars for success:

1. Secure Land Tenure

Long-term leases or ownership arrangements encourage investment and sustainability.

2. Municipal Support

Fencing, soil testing, permitting, and branding reduce barriers to entry for farmers.

3. Institutional Integration

Schools, hospitals, and city agencies can serve as both hosts and consumers of urban farm products.

4. Community Ownership

Whether through volunteer models or cooperatives, urban farms thrive with local buy-in.

The City of Berkeley can combine these insights to shape a hybrid model that blends public stewardship, entrepreneurial partnerships, and equity-focused zoning reform. By learning from San Francisco, Tokyo, Boston, and its own backyard, the City of Berkeley can develop a tailored urban agriculture system that uplifts communities, reduces emissions, and grows local wealth one parcel at a time.

All highlight the need for tenure security, technical support, and integrated policy planning.

Policy Alternatives & Decision Framework

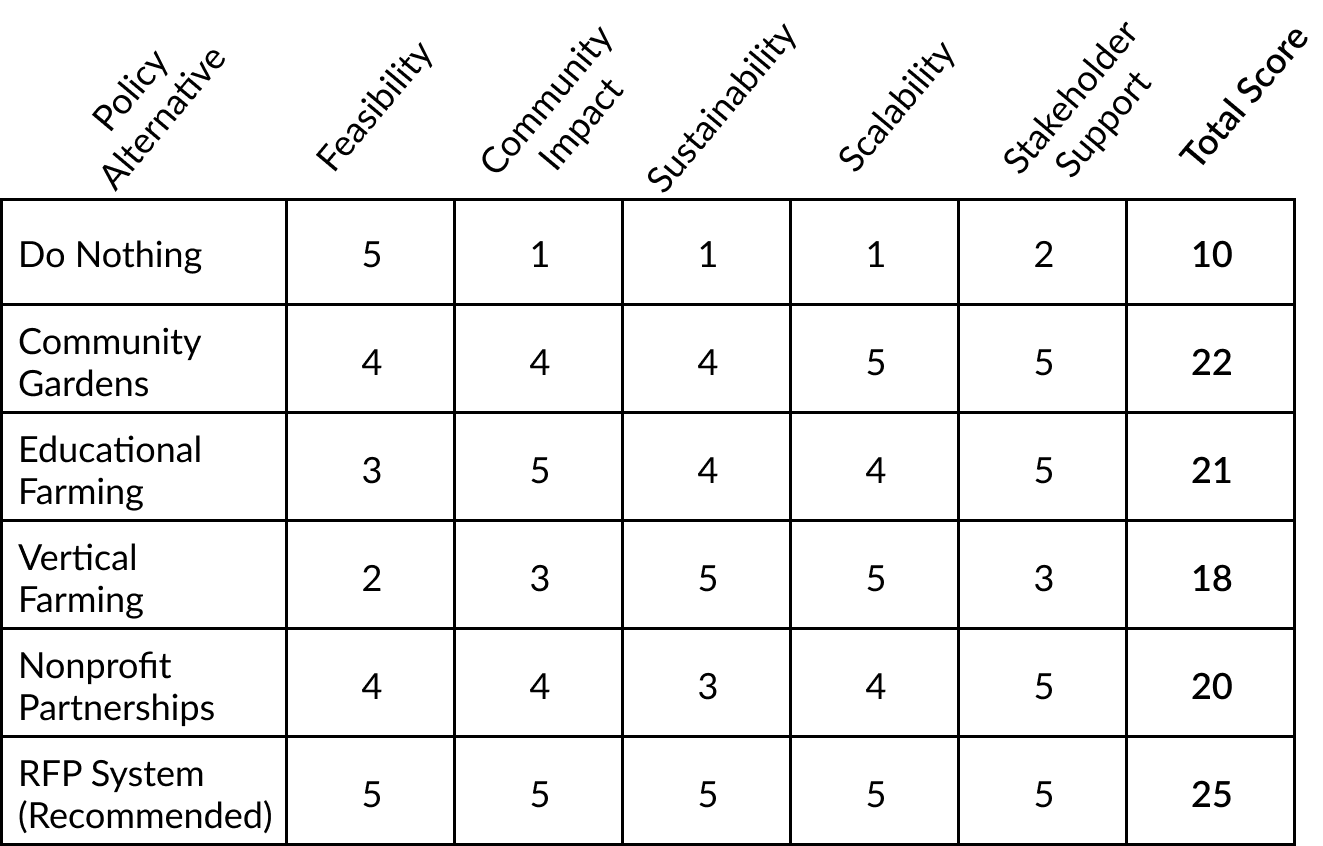

In assessing pathways to advance urban agriculture on underutilized city-owned properties, six distinct policy alternatives emerge. Each offers varying levels of feasibility, sustainability, and potential impact across the City of Berkeley’s neighborhoods. To guide effective decision-making, this section outlines each alternative, establishes evaluation criteria, and projects expected outcomes.

Construct the Alternatives

2. Community Gardens

This alternative proposes converting select city-owned lots and school properties into community-managed gardens. Operated by neighborhood groups, nonprofits, or cooperatives, these gardens would empower residents to grow produce for personal consumption or local markets. Community gardens offer low barriers to entry, require minimal infrastructure, and enhance local control over food access.

3. Educational Farms

Partnering with the Berkeley Unified School District and UC Berkeley, this model would integrate urban farming into the educational environment. School and university grounds could host working farms that serve dual purposes: cultivating food and teaching students about agriculture, environmental science, and sustainability. These farms would support curriculum development while modeling best practices for community-scale food systems.

4. Vertical Farming

Vertical farming solutions—such as hydroponic systems on rooftops or building facades—offer the potential for high-yield food production with minimal land use. These technologically advanced operations can function year-round and maximize space efficiency, particularly in dense urban areas. However, they also demand specialized knowledge, energy inputs, and capital investment.

5. Partnerships with Nonprofits

Many nonprofit organizations in the City of Berkeley have expertise in food justice and urban sustainability. This alternative would formalize partnerships with such groups to manage urban farms, conduct training, and distribute food. Leveraging existing community networks could streamline implementation and ensure equitable access to resources.

1. Do Nothing

This baseline alternative reflects the current state in which the City of Berkeley does not proactively intervene. Under this scenario, properties remain underutilized, and opportunities for food production, education, or environmental improvements are forgone. While this option incurs no immediate fiscal or administrative cost, it also fails to address pressing needs related to food insecurity, climate resilience, and community engagement.

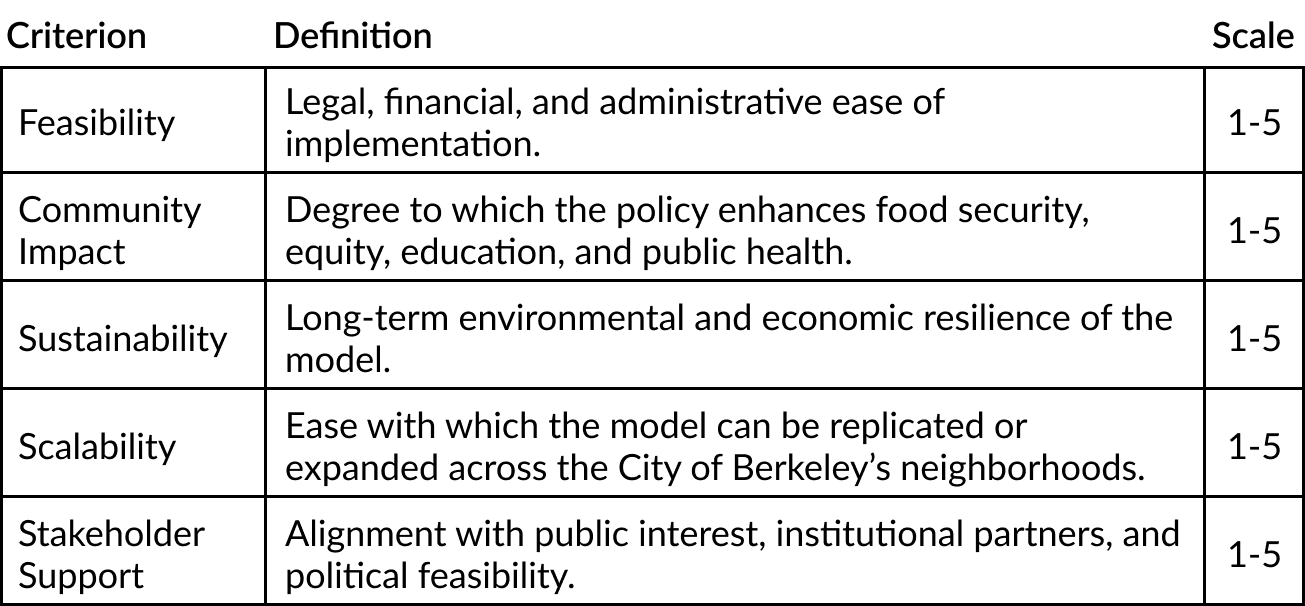

To evaluate each alternative, a five-point Likert scale is used across five criteria. Each option is scored from 1 (Very Low) to 5 (Very High), based on its capacity to meet key objectives. The selected criteria are:

Feasibility

Reflects the legal, financial, and logistical practicality of implementation. Higher scores denote minimal regulatory barriers, reasonable costs, and administrative ease.

Community Impact

Measures each alternative’s ability to enhance food security, promote educational outcomes, and improve public health. A higher rating indicates wide-reaching benefits across multiple community indicators.

Sustainability

Evaluates both environmental performance (e.g., emissions, water use, biodiversity) and economic durability. Alternatives scoring high in this category support long-term viability and resilience.

Scalability

Assesses how easily a project can be replicated or expanded throughout the City of Berkeley’s neighborhoods. A high score denotes flexibility, adaptability, and broad applicability.

Stakeholder Support

Reflects community interest, institutional buy-in, and alignment with resident priorities. A top score indicates strong partnerships and public enthusiasm.

Each policy option will be scored using this framework to support transparent and data-driven selection.

Project the Outcomes

Adopting a citywide urban agriculture strategy centered on a formal Request for Proposals (RFP) system to lease underutilized city-owned land for at least five years will yield profound benefits for the City of Berkeley’s food system, economy, and environment. This RFP system, overseen by the Office of Economic Development, will enable the City of Berkeley to proactively match properties with qualified community organizations, entrepreneurs, and farmers to cultivate edible and non-edible crops for local distribution.

Key outcomes anticipated from implementing this RFP-driven urban agriculture strategy in the City of Berkeley include:

Expanded Local Food Production:

RFP agreements will activate idle public land, enabling farmers and cooperatives to grow fresh produce, herbs, and flowers for direct sale to Berkeley residents, local markets, and institutions.

Small Business Growth and Job Creation:

Leasing land to local agricultural enterprises will stimulate green entrepreneurship, particularly among BIPOC farmers, women-owned businesses, and food justice advocates.

Reduced Legal Risk to the City of Berkeley:

Clear lease terms and soil testing standards under the RFP framework will shift liability away from the City of Berkeley, allowing it to act as a responsible land steward rather than a food producer.

Sustainable Land Use and Environmental Resilience:

Formerly neglected lots will contribute to biodiversity, stormwater management, and carbon sequestration through regenerative practices.

Community Engagement and Ownership:

Residents will take pride in seeing formerly vacant land converted into vibrant, productive spaces—fostering deeper connections to local food systems and neighborhood identity.

Scalable and Replicable Framework:

The RFP model enables streamlined policy replication across other municipalities. By publishing open calls, establishing transparent scoring criteria, and offering in-kind city support (e.g., website, branding, soil testing), the City of Berkeley can build a resilient food economy that scales equitably.

This model builds on successful practices observed in Setagaya, Japan, where the municipal government leases public land to local agricultural cooperatives and individual farmers through long-term agreements. In Setagaya, the city provides essential support infrastructure—such as fencing, irrigation, and signage while maintaining land ownership. Farmers produce vegetables, flowers, and trees, selling them directly to residents, schools, and restaurants. This approach ensures food security, landscape beautification, civic pride, and a circular local economy.25

Secondarily, several overarching outcomes are anticipated across the alternatives. The most promising models—such as educational farms and community gardens—are expected to result in:

- Increased local food production, reducing reliance on distant food systems and enhancing neighborhood-level resilience.

- Greater access to fresh produce, particularly in areas identified as food deserts, improving public health and dietary equity.

- Enhanced educational opportunities, as school farms and community programs integrate hands-on learning about agriculture and sustainability.

- A measurable reduction in carbon emissions, by shortening food supply chains and encouraging local plant-based diets.

- More productive use of public lands, transforming vacant or blighted parcels into vibrant community assets.

- Elevated community engagement and empowerment, as residents take part in growing food, shaping land-use decisions, and co-managing public resources.

These outcomes will inform subsequent recommendations, with an emphasis on scalability, cost-effectiveness, and alignment with the City of Berkeley’s broader sustainability and equity goals.

Criteria Applied (Likert Scale):

Community Impact

Sustainability

Scalability

Stakeholder Support

Feasibility

Outcomes: Community gardens and educational farms scored highest for feasibility and impact, while vertical farming excelled in scalability but faced cost barriers. A hybrid, phased model provides the best path forward.

Recommendations and Implementation

Primary Recommendation:

Issue RFPs for public land use to for-profit and nonprofit agricultural operators. The City of Berkeley will:

- Provide a centralized website and branding (logo, farm directory, online ordering).

- Install fencing and conduct baseline soil testing.

- Offer long-term leases with tiered oversightInclude non-edible plant sites (flower/tree farms) for contaminated soils.

This model, successfully used in Setagaya City, Japan, positions the City of Berkeley as a landlord and facilitator rather than operator. It reduces liability and attracts private investment.26

Estimated Budget: 500K initial phase, with cost recovery through partnerships, grants, and reduced food assistance expenses.

From Policy to Implementation

To transition from policy design to execution, the City of Berkeley must take the following concrete steps:

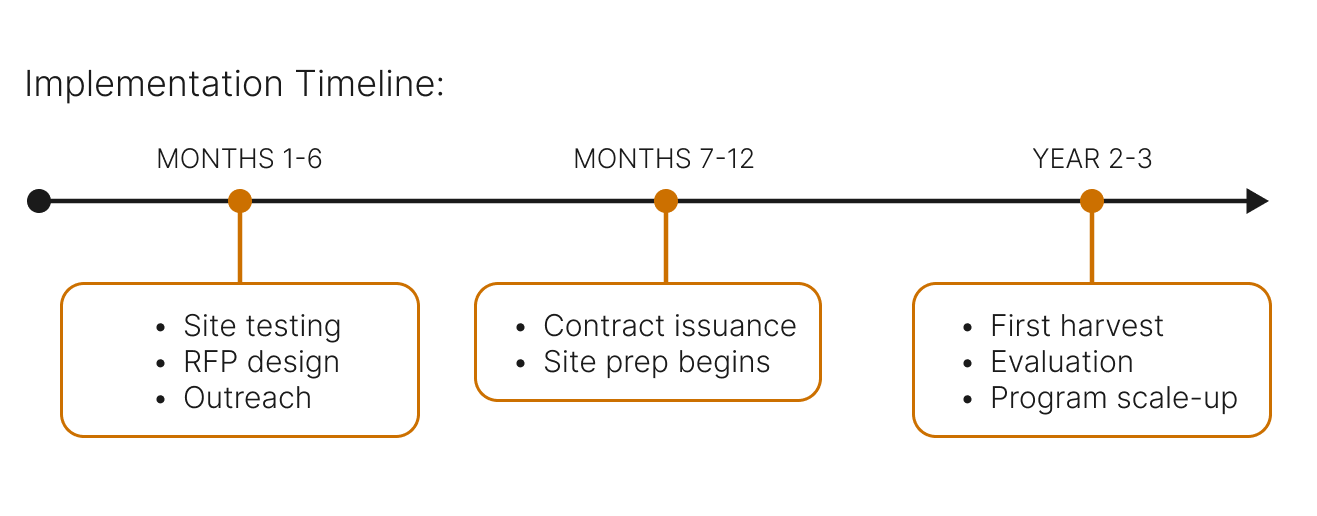

2. Soil and Environmental Assessment (immediately):

The City of Berkeley must commission soil testing for all 57 underutilized city properties to assess viability and contamination levels. Parcels unsuitable for edible crop production could be redirected toward flower farms, pollinator habitats, or native tree nurseries, reducing liability and expanding greening efforts.

3. Build Digital Infrastructure (concurrent with RFP):

The City of Berkeley should fund the development of a centralized website to:

- Publicize the Urban Agriculture RFP and ongoing program updates.

- Feature farm profiles, community engagement tools, and real-time updates.

- Enable residents and businesses to purchase directly from participating urban farms, improving visibility and economic sustainability.

4. Develop a Visual Identity and Community Brand (within 4 months):

A city-commissioned logo, design toolkit, and outreach materials should help unify the program under a recognizable brand. This will increase visibility, build trust, and signal institutional support.

5. Install Critical Infrastructure (based on site selection):

Fencing, water access hookups, and signage should be installed by the City of Berkeley as part of its commitment to being a responsible steward and partner. This public investment in infrastructure reduces entry barriers for new growers.

6. Pilot Implementation and Evaluation (within 12 months):

Once parcels are matched to operators through the RFP, the City of Berkeley should monitor outcomes using pre-identified KPIs such as food yield, neighborhood participation, and community health improvements. These pilot results will inform a broader scaling strategy in subsequent fiscal years.

1. Launch the RFP Process (within 3–6 months):

The Office of Economic Development should release a Request for Proposals (RFP) inviting urban farming organizations, cooperatives, and entrepreneurs—especially those already participating in Berkeley farmers markets—to lease designated city-owned parcels for cultivation. The RFP should include favorable leasing terms (e.g., $1/year pilot leases), clear operating standards, and community benefit requirements.

Risk Analysis and Mitigation

Identified Risks:

- Soil toxicity

- Legal liability (see dedicated section)

- Community opposition

- Scope creep

- Funding shortages

Mitigation Strategies:

- Soil testing and remediation/raised beds

- Standardized MOUs with liability protections

- Early and sustained engagement with neighbors

- Defined pilot phases and deliverables

- Securing private/public partnership agreements, CDFA, and private grants

Legal Liability and Risk Management

Legal Vulnerabilities:

- Contaminated soils → use raised beds + testing

- Food illness risks → require GAP-certified training

- Trip/fall or injury risks → insurance and signage

- Clear indemnification clauses in MOUs

Mitigation:

- Partner with City Attorney to draft a model urban ag lease/license

- Provide city-funded site testing and shared insurance resources for smaller orgs

Evaluation and Monitoring Framework

Key indicators:

Pounds of food produced

Jobs created

Education hours delivered (schools, public)

Community satisfaction (survey)

Number of operational sites

Metrics will be gathered semi-annually and reported to the City Council with course-correction mechanisms.

Future Research Directions

This memo opens the door to several areas of further inquiry that would strengthen the City of Berkeley’s urban agriculture policy ecosystem:

2. Urban Agriculture and Housing Co-Location

Integrating agriculture into affordable housing developments drawing inspiration from international examples like Setagaya City, Japan presents a unique opportunity for future policy design and site planning in the City of Berkeley.

3. Economic Multiplier Effects

A comprehensive economic impact study could quantify the ripple effects of city-supported urban farming on local business ecosystems, job creation, and food supply chain resilience.

4. Food Access and Health Metrics

Future research should analyze how increased proximity to urban farms affects residents’ nutritional intake, mental health, and food security, particularly in BIPOC and low-income communities.

5. Urban Heat Island and Biodiversity Effects:

As the climate crisis deepens, understanding how urban farming mitigates urban heat, improves soil permeability, and restores native habitats will be crucial to integrating agriculture into the City of Berkeley’s broader environmental resilience strategy.

1. Long-Term Land Tenure and Community Land Trust Models

Further study is needed on models that guarantee long-term access to land while maintaining public ownership—such as community land trusts or cooperatively managed stewardship agreements. Research could also examine potential for reparative land access models rooted in racial equity.

Conclusion

The City of Berkeley must move beyond legacy food procurement and land use models that fail to meaningfully contribute to our public food supply or meet the urgency of our climate and equity goals. A centralized Request for Proposals (RFP) system, administered by the Office of Economic Development, offers a transparent, strategic, and accountable mechanism for leasing city-owned properties to local urban agriculture initiatives. Unlike fragmented or ad hoc approaches, the RFP system aligns public land use with measurable outcomes in food security, job creation, and environmental resilience. This model not only empowers local farmers but also positions the City of Berkeley to lead the nation in integrating food justice into city governance. The City of Berkeley has the policy vision, the land, and the leadership to transform urban agriculture from a fringe concept to a core city strategy. By activating neglected spaces, the City of Berkeley can simultaneously combat food insecurity, stimulate equitable economic growth, and make good on its climate commitments. This memo offers a blueprint grounded in data, driven by community, and designed for long-term impact. The time to plant is now.

Appendices

Interview Questions: Urban Agriculture in Berkeley

1. How would you describe the current landscape of urban agriculture in the City of Berkeley today? What are its greatest strengths and challenges?

2. From your perspective, what are the most underutilized opportunities for growing food on public or city-controlled land?

3. How effective has Berkeley’s 2018 Urban Agriculture Ordinance been in enabling or supporting local growing efforts?

4. What zoning or land-use policies do you believe help—or hinder—urban farming in the City of Berkeley?

5. Do you think the City of Berkeley should play a more active role in supporting urban agriculture? If so, how?

6. How can we ensure urban agriculture initiatives directly benefit low-income communities and address food insecurity in the City of Berkeley?

7. What kinds of legal or liability concerns should the City of Berkeley consider when authorizing food production on public land?

8. How do you see partnerships with Berkeley Unified School District, UC Berkeley, or local nonprofits strengthening this work?

9. What infrastructure is most needed to support sustainable, long-term urban agriculture—water access, soil remediation, training, land security, etc.?

10. What lessons can the City of Berkeley learn from other cities (e.g., San Francisco, Chicago, Philadelphia) that have integrated urban agriculture into their planning?

11. What kind of community engagement or participatory planning would be most meaningful for advancing urban agriculture in the City of Berkeley?

12. Are there specific neighborhoods or districts in the City of Berkeley where you think urban farming should be prioritized? Why?

13. How would you define success for an urban agriculture program led or supported by the City of Berkeley?

14. What funding strategies or financial models do you think are most viable for expanding urban farming on public land?

15. Finally, if you had one recommendation for the City Council or city staff to act on immediately, what would it be?

16. How should the City of Berkeley prioritize between community gardens, educational farms, commercial urban agriculture, and vertical farming?

17. What are the biggest barriers to securing long-term land tenure for urban agriculture projects on city-owned land in the City of Berkeley?

18. In your experience, how receptive have city agencies (e.g., Planning, Public Works, Parks) been to integrating urban farming into city operations or land use planning?

19. What role do you believe city-funded soil testing and environmental assessments should play in supporting safe urban agriculture?

20. How can the City of Berkeley design an equitable lease or licensing framework that allows community groups to access city land without excessive red tape?

21. Do you think public support for urban agriculture is strong in the City of Berkeley? What factors influence community trust and engagement in these projects?

22. How can the City of Berkeley measure the success of an urban agriculture program beyond just pounds of produce—e.g., health outcomes, job creation, environmental impact?

23. What should the City of Berkeley do to prepare for legal liability issues related to food safety, property access, or volunteer injury on public land?

24. What kinds of workforce development or training programs could complement the expansion of urban agriculture in the City of Berkeley?

25. Based on your knowledge of other successful models (like Alemany Farm, Oosterwold, or Boston Medical Center’s rooftop farm), what would you encourage the City of Berkeley to adopt or avoid?

Evaluation Framework: Likert Scale Scoring Matrix

To assess the viability and strategic impact of each urban agriculture policy alternative, this memo uses a 5-point Likert scale across five evaluation criteria. Each alternative is scored from 1 (Very Low) to 5 (Very High) on each criterion, allowing for a comparative and transparent decision-making process.

Example Evaluation Table

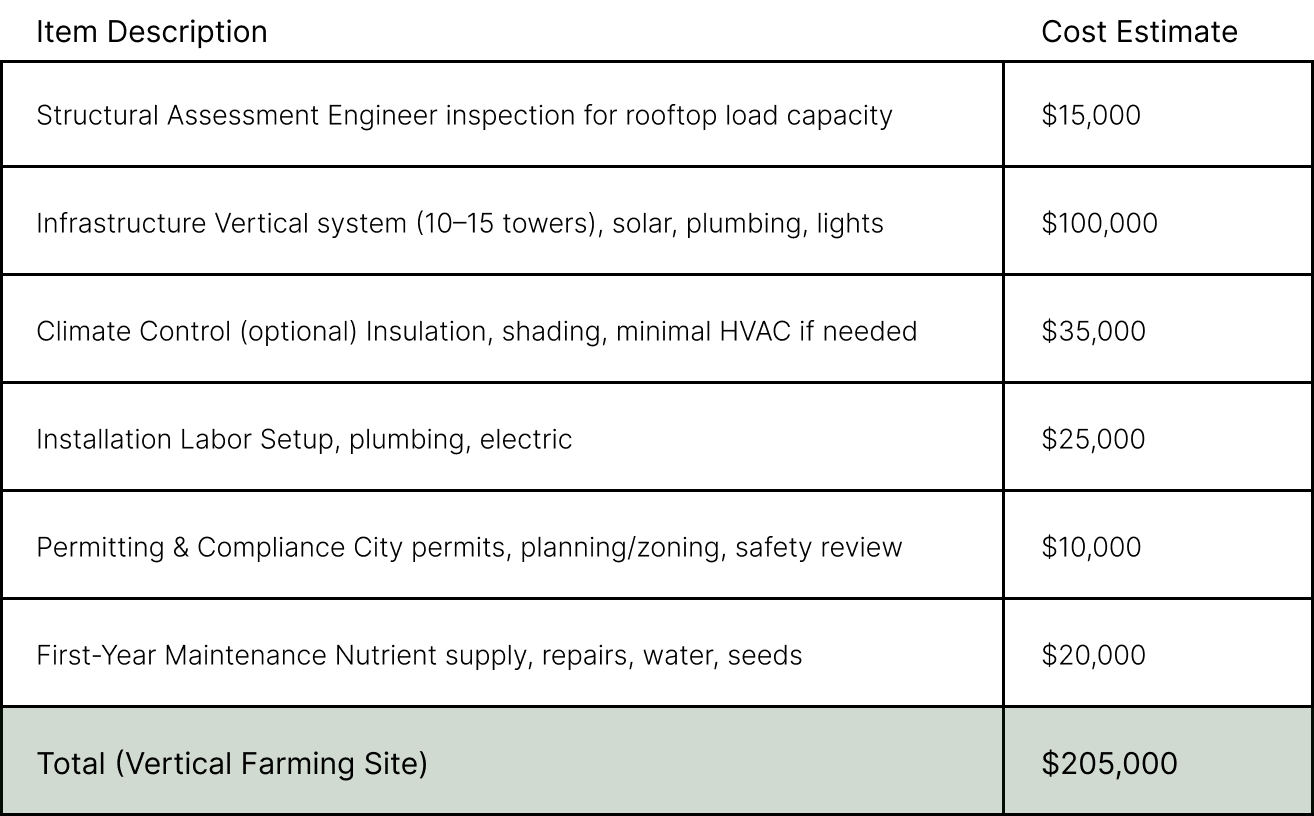

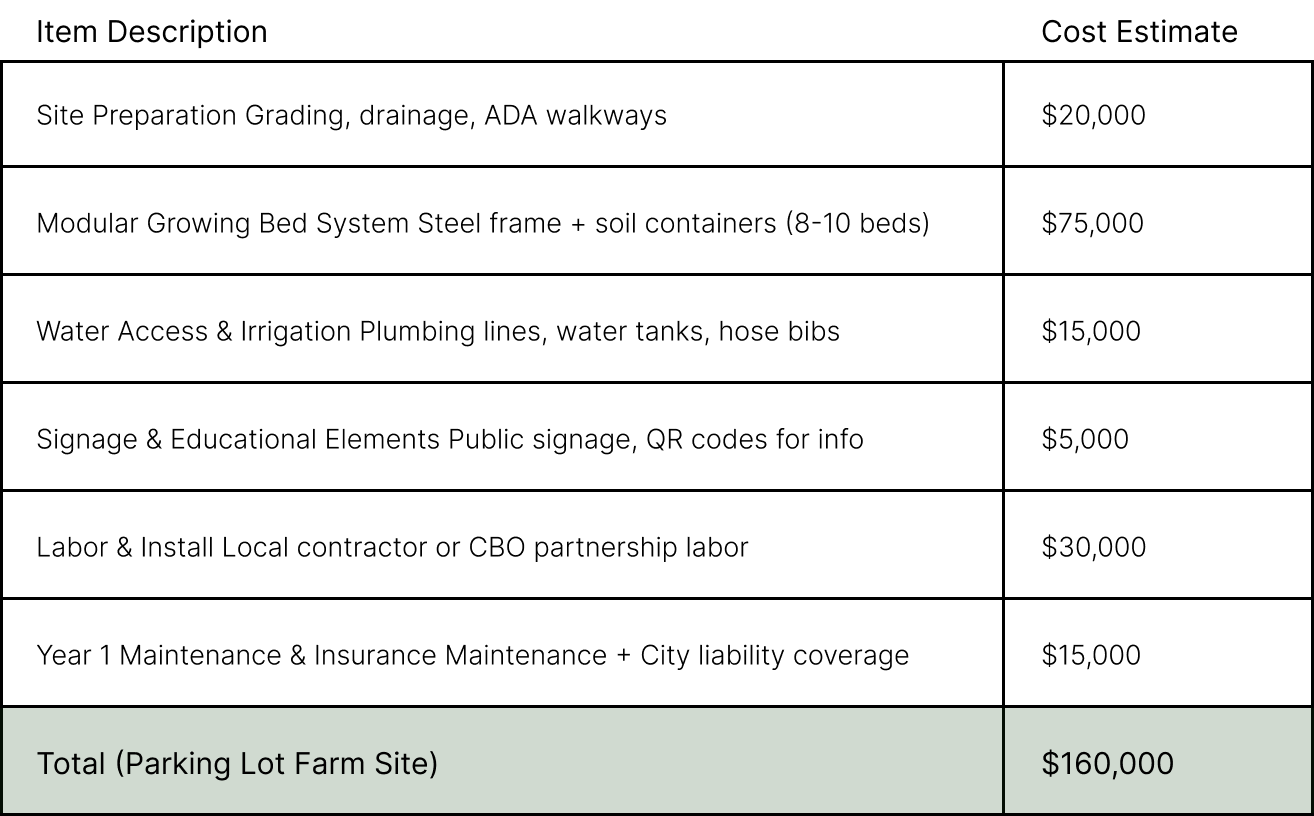

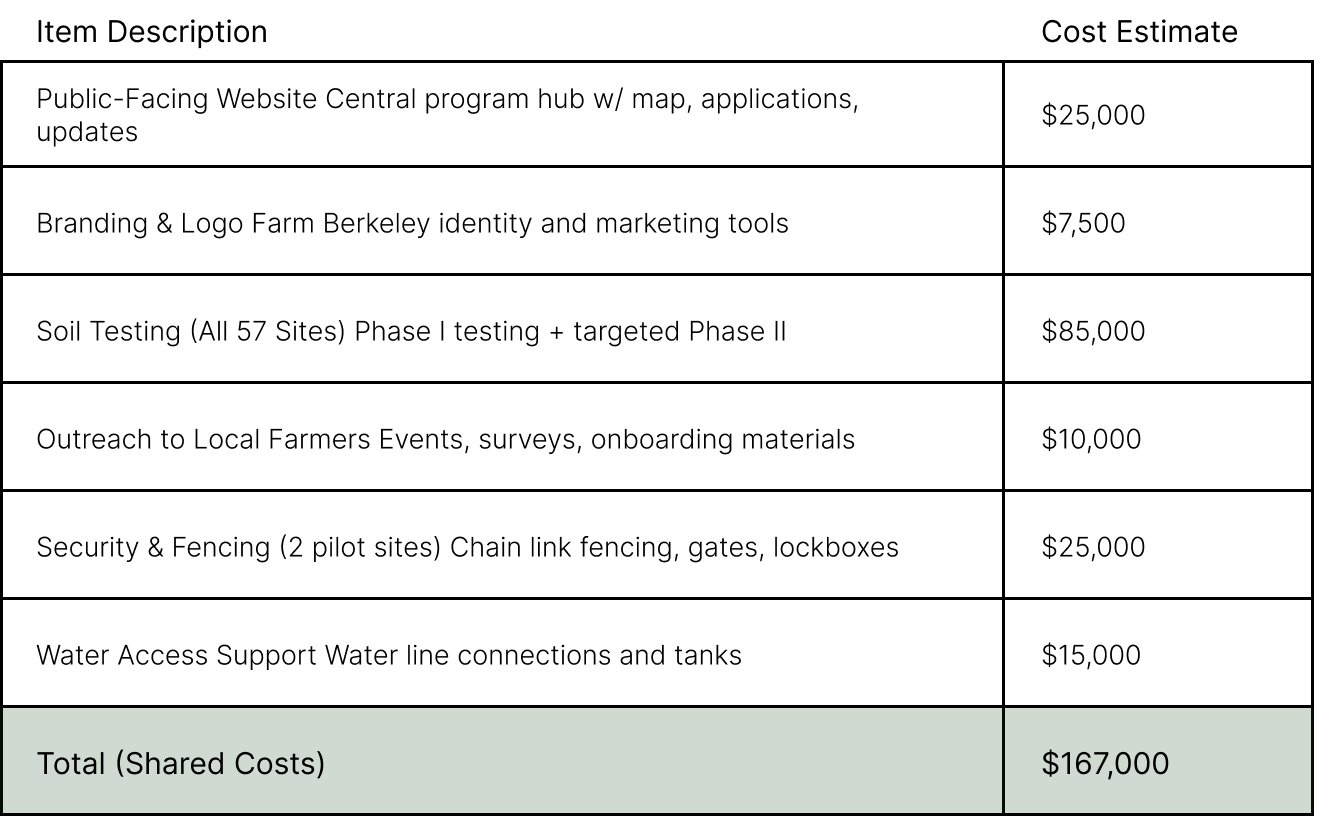

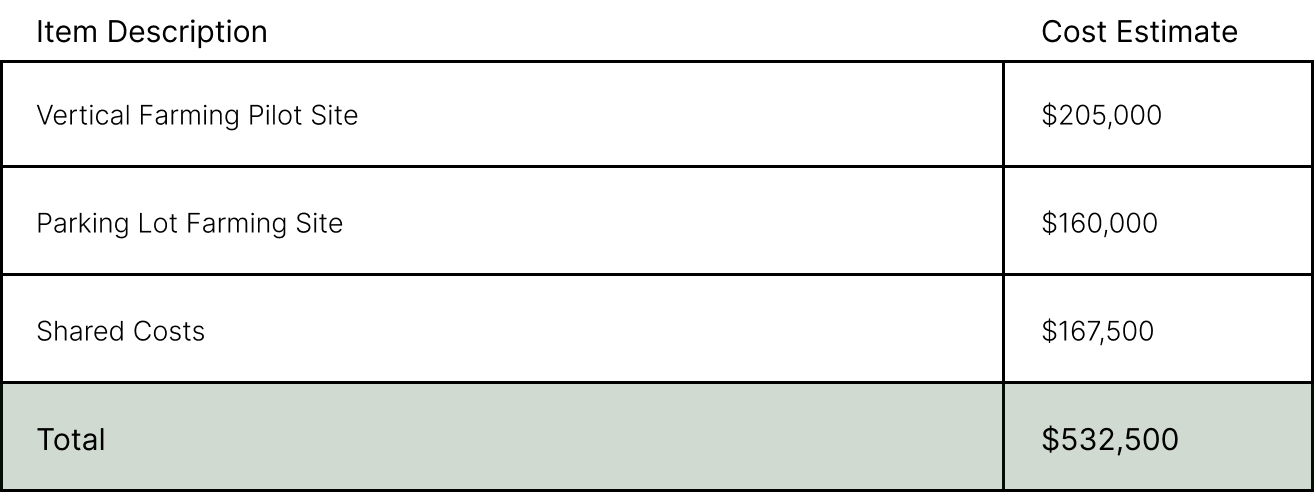

Secondary Budget Proposal: Vertical Farming & Parking Lot Farming Pilot

City of Berkeley Urban Agriculture Expansion — Phase II

Overview:

This budget supports a Phase II pilot for installing vertical farming systems and elevated farming structures on underutilized parking lots and rooftops in the City of Berkeley. These projects will complement soil-based farming initiatives and extend food production capacity where traditional land access is limited.

Key Components of Phase II Pilot:

1. Pilot Vertical Farming Installation

Location

Rooftop of a city-owned facility (e.g., Berkeley Civic Center or nearby multi-use municipal building).

System

Hydroponic or aeroponic vertical towers (indoor/outdoor hybrid with solar augmentation).

Output Goal

~2,000–3,000 lbs of leafy greens/herbs annually.

2. Farming Structure Over Parking Lot (Elevated Bed/Pergola Style)

Location

City-owned parking lot (e.g., Adeline & Alcatraz or MLK & Dwight)

System

Elevated modular growing beds on platforms allowing continued parking use.

Output Goal

Modular leafy greens, tomatoes, edible flowers, etc. grown seasonally.

Shared Programmatic Costs (for both vertical and elevated models):

Phase II Pilot Program – Total Estimated Budget

Strategic Goals:

Demonstrate how urban space innovation can boost food production without displacing existing infrastructure.

Promote partnerships with local farms that participate in Berkeley’s farmers markets and CSA programs.

Establish scalable models for rooftop, vertical, and dual-use urban farming in high-density areas.

Distribution of Underutilized Property Types

References

Documents:

1. Berkeley City Council. (2023, May 23). Annotated agenda - City Council meeting. City of Berkeley. Retrieved from https://berkeleyca.gov/sites/default/files/city-council-meetings/2023-05-23%20Annotated%20Agenda%20-%20Council.pdf

2. City of Berkeley. (2023, June 27). Berkeley Food Utility and Access. City of Berkeley. Retrieved from https://berkeleyca.gov/sites/default/files/documents/2023-06-27%20Item%2045%20Berkeley%20Food%20Utility%20and%20Access.pdf

3. Berkeley City Council. (2019, November 12). Additional funding for Berkeley’s urban agriculture training programs. City of Berkeley. Retrieved from https://berkeleyca.gov/sites/default/files/documents/2019-11-12%20Item%2016%20Additional%20funding%20for%20Berkeley.pdf

4. City of Berkeley. (n.d.). Berkeley FARM Program [Slide presentation]. Google Slides. Retrieved from https://docs.google.com/presentation/d/14if0KnYVQHrF_6cqbp0qhsZrpzyy1pga0G6xRWCAUQU/edit

5. Berkeleyside. (2025, January 31). Berkeley 2025 audit: City disorganized in property management. Berkeleyside. https://www.berkeleyside.org/2025/01/31/berkeley-2025-audit-city-disorganized-property-management

6. Takami, D. (1986, April 2). ID Community Garden: “The land could just wash away again.” International Examiner (1976-1987), p. 1.

7. Duncan, M. (2012, June 14). Veterans garden vies for $25k prize. The El Chicano Weekly, 49(24)

8. Jahrl, I., Moschitz, H., & Cavin, J. S. (2021). The role of food gardening in addressing urban sustainability: A new framework for analysing policy approaches. Land Use Policy, 108, 105564. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2021.105564

9. Isenhour, C., McDonogh, G., & Checker, M. (2015). Sustainability in the global city: Myth and practice. Cambridge University

10. Mazzucato, M. (2013). The entrepreneurial state: Debunking public vs. private sector myths. Anthem Press

Press Interviews:

1. Bartlett, B. (2025, January 27). Personal interview.

2. Desai, N. (2025, January 26). Personal interview.

3. Chang, J. (2025, January 28).

4. Banks, A. (2025, January 29). Personal communication [Email].Manages Oxford Tract, a Berkeley student-run farm. Started in guerrilla farming in Oakland to access fresh food and now runs a farm and program supporting the community.

6. Edwards, A. (2025, January 29). Personal communication [Email].USDA urban agriculture representative. Setting up the Bay Area service center and programs in Oakland.

7. University of California, Berkeley. (n.d.). Gill Tract & Clark Kerr student-run farms. Student-run farms at UC Berkeley. Owned by the university but receive no financial support. Under constant threat of being reclaimed for student housing and/or development.

8. Rachel Brand Curriculum Manager at College of MarinBerkeley, California, United States

9. Nina F. Ichikawa Nina F. Ichikawa is the former Executive Director and before that, Policy Director for the Berkeley Food Institute, an interdisciplinary research and action center on the campus of the University of California at Berkeley ninafichikawa.com

10. Joann Letz, Owner Bluma Flower Farm

11. Executive Director, Daniel Miller Spiral Gardens Community Farm

12. Rich Hannan BUSD School Nutrition Director

13. Tracy Randolph Berkeley Farmer

14. Dakh Jones Local Bee Keeper and Honey Farmer

15. Sarah Miller Moore Manager, Office of Energy and Sustainable Development

Government & Policy Documents:

1. City of Berkeley. (2021). Accelerating transition to plant-based foods. https://berkeleyca.gov/sites/default/files/documents/2021-07-27%20Item%2022%20Accelerating%20transition%20to%20Plant-Based%20Foods.pdf

2. City of Berkeley. (2020). Agenda packet - Agenda committee (August 31, 2020). https://berkeleyca.gov/sites/default/files/legislative-body-meeting-agendas/2020-08-31%20Agenda%20Packet%20-%20Agenda%20Committee.pdfMilan Urban Food Policy Pact &

Related Documents:

3. Milan Urban Food Policy Pact (MUFPP). (2021). Regionalisation process action plan 2021-23. https://www.milanurbanfoodpolicypact.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/MUFPP-Regionalisation-Process-Action-Plan-2021-23.pdf

4. Milan Urban Food Policy Pact (MUFPP). (n.d.). Our cities. https://www.milanurbanfoodpolicypact.org/our-cities/

5. International Panel of Experts on Sustainable Food Systems (IPES-Food). (2017). What makes urban food policy happen? Insights from five case studies. https://www.ipes-food.org/_img/upload/files/Cities_full.pdf

Climate-Friendly & Sustainable Food Policy:

6. Sentient Media. (n.d.). U.S. cities adopting climate-friendly food policies. https://sentientmedia.org/us-cities-climate-friendly-food/

7. C40 Knowledge Hub. (n.d.). Milan Urban Food Policy Pact. https://www.c40knowledgehub.org/s/article/Milan-Urban-Food-Policy-PactAcademic & Research Reports:8. Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO). (n.d.). Milan Urban Food Policy Pact: Open knowledge report. https://openknowledge.fao.org/server/api/core/bitstreams/0f7b5e22-5f9d-4087-a4ce-46fdffd79060/content

9. Nature. (2024). Urban food policy trends. https://www.nature.com/articles/s43016-024-01109-4Institutional

Membership & Access Resources:

10. UC Berkeley Alumni Association. (n.d.). Membership FAQs. https://alumni.berkeley.edu/join/membership-faqs/

11. Berkeley Faculty Club. (n.d.). Membership categories and dues. https://www.berkeleyfacultyclub.com/membership/categories/dues

12. Berkeley Property Owners Association (BPOA). (n.d.). Membership information. https://www.bpoa.org/membership-information

University & Student Resources:

13. UC Berkeley Admissions. (n.d.). Check your application status. https://admissions.berkeley.edu/status/

14. UC Berkeley Recreational Sports. (n.d.). Visit us. https://recwell.berkeley.edu/visit-us/

15. UC Berkeley Recreational Sports. (n.d.). Membership FAQs. https://recwell.berkeley.edu/membership-faqs/

Social & News Articles:

16. NYC Food Policy Center. (n.d.). Milan Urban Food Policy Pact. https://www.nycfoodpolicy.org/milan-urban-food-policy-pact/

17. LinkedIn. (2024). Milan to host the next MUFPP global forum. https://www.linkedin.com/posts/food-trails_milan-to-host-the-next-mufpp-global-forum-activity-7292479471008284673-aMXx

18. EAT Forum. (n.d.). EAT MUFPP global forum. https://eatforum.org/learn-and-discover/eat-mufpp-global-forum/

Food Security and Food Justice Initiatives in Berkeley:

1. Driscoll, L. (2017). Urban farms: Bringing innovations in agriculture and food security to the city. Berkeley Food Institute. https://food.berkeley.edu/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/BFI_UrbanAgPolicyBrief_8.1.17-

2.-FINAL-ELECTRONIC.pdf1. Berkeley Food Network. (n.d.). Meeting basic needs post-COVID: Looking forward to collective action. https://www.berkeleyfoodnetwork.org/meeting-basic-needs-post-covid-looking-forward-to-collective-action/

3. Sentient Media. (n.d.). How one small city in California is going plant-based. https://sentientmedia.org/how-one-small-city-in-california-is-going-plant-based/

4. UC Berkeley School of Law. (n.d.). Food Justice Project – Student-Initiated Legal Services Projects (SLPS). https://www.law.berkeley.edu/experiential/pro-bono-program/slps/current-slps-projects/food-justice-project/

5. Berkeley Food Network. (n.d.). What we do: Programs. https://www.berkeleyfoodnetwork.org/what-we-do/programs/

6. City of Berkeley. (2021). Support Vision 2025 for Sustainable Food Policy. https://berkeleyca.gov/sites/default/files/documents/2021-03-09%20Item%2019%20Support%20Vision%202025%20for%20Sustainable%20-%20Rev%20Kesarwani.pdf

7. University of California Office of the President (UCOP). (n.d.). Food access & security: Best practices. https://www.ucop.edu/global-food-initiative/best-practices/food-access-security/index.html

Acknowledgements

I would like to express my deepest gratitude to the individuals and organizations who generously shared their time, insights, and expertise to support this research. This project would not have been possible without the guidance and collaboration of so many in the Berkeley community.

Thank you to Vice Mayor Ben Bartlett and his office, whose visionary leadership in sustainability and food justice continues to inspire transformative policy work. I am especially grateful to Daniel Miller of Spiral Gardens, Rich Hannan of the Berkeley Unified School District, and Tracy Randolph, whose work and reflections grounded this project in lived experience and deep community knowledge.

I also want to thank Dr. Neena Ishikowa for her leadership and input on environmental alignment with the City of Berkeley’s F.A.RM. Bill and Vision 2025. Additional appreciation goes to Dakh Jones and the network of local urban farmers and organizers who lent their stories, data, and wisdom to this work.

Dr. Erika Weisinger and all my colleagues who supported this capstone project with critical feedback and encouragement.Finally, I am grateful to the team at The Moore Working Group, whose commitment to public good continues to shape my professional values and aspirations.